Combining the complexities of nature and communities

In the world of forest ecosystems, lichen serves as both sentinel and sustainer. Yet for the Saulteau Creek community living near these lush landscapes, this symbiotic life form embodies far more: a linchpin in a complex tapestry of science, culture, and lifeblood for the iconic caribou. This complex organism is what brought Carmen Richter, Y2Y’s Sarah Baker Memorial Grant recipient in 2022, to her critical work.

Carmen is a member of Saulteau First Nations, a rural community in Treaty 8 territory of northeast B.C. Growing up in an Indigenous community, her love for the outdoors was kindled by joining in her family’s traditional activities. Early on, she learned from nature by helping her family with tasks like hauling wood and spending time on the land. These experiences sparked a deep connection to the landscapes and wildlife within her community.

In school, Carmen found her passion in biology, drawn to it because it brought her outside to stay connected to the land. This interest led her to pursue a master’s degree at the University of British Columbia – Okanagan Campus, where she combined her love for biology with her commitment to Indigenous rights and land sovereignty.

Currently, Carmen is creating an Indigenous Guardians program for her community. She’s also the author of Maskihkîya, translating to ‘Strength of the Earth’, a book on ethnobotany. Her work also includes assisting in the development of new protected areas and restore caribou populations, always keeping the goals of her community at heart.

Carmen’s research in applied conservation is always aimed at what’s best for her community’s way of life and the health of their land. The purpose of her master’s research came from and was informed from the experiences of the community in their lichen harvest.

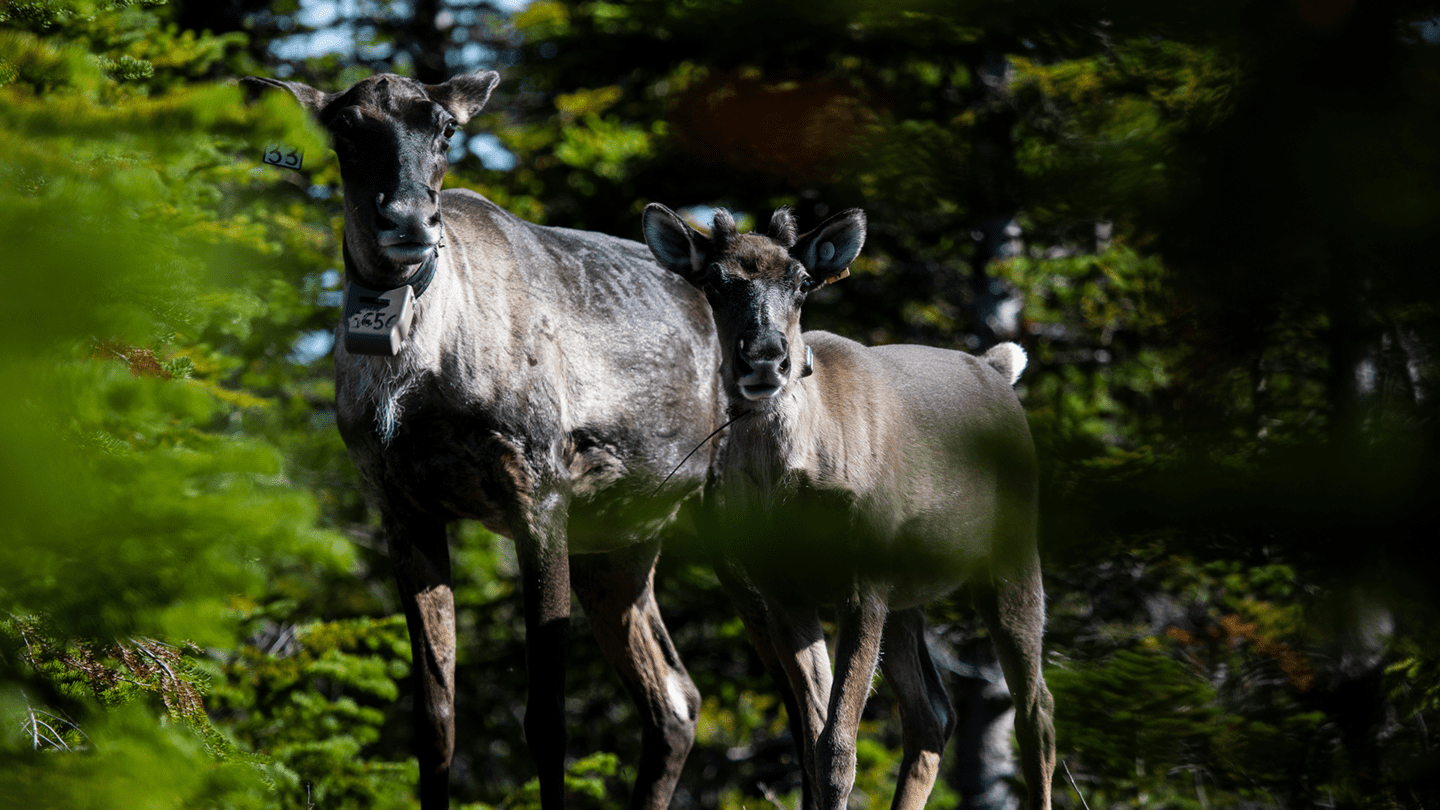

Reliable lichen growth is crucial for the survival of caribou. The West Moberly and Saulteau First Nations’ conservation efforts have been vital in bringing the Klinse-Za caribou from near extinction by making sure these animals have the food they need. Lichen is a key part of their diet, and without it, caribou populations can’t recover.

One question lingered in the community’s mind: Within such a big territory, wouldn’t it be nice to to be able to predict where lichen will grow in the future? Being able to find predictable sources of lichen is important. This vital food source helps sustain recovering caribou populations, especially mothers and their young.

Carmen’s community recognized a significant gap: there was no data on how much lichen would be available to support caribou recovery and conservation efforts in the long term. This realization directly led to a lack of strategic planning for sustainable collection of lichen. The need for a strategic approach was what inspired Carmen to return to school and develop her master’s thesis around creating a plan for sustainable lichen collection.

The Lifeline of Lichen

Lichen, while simple, is a crucial food source that serves as a lifeline for the caribou — a cornerstone species deeply embedded in the community’s culture and livelihood. During the calving season, caribou naturally seek out lichen-rich areas, a behavior the community has honored and integrated into their conservation efforts.

Thus, safeguarding these patches becomes more than a conservation tactic. It’s a holistic approach tied to the very wellness of the community.

Carmen’s research has enabled her to create detailed maps of lichen across various landscapes. By doing so, she has identified areas where the existence of lichen overlaps with land designated for forestry, mining, and energy projects. This overlap poses a potential threat to caribou recovery efforts, as these lands are at risk of being developed without consideration for their ecological importance.

Building a predictive model: Bayesian mapping

Bayesian modeling is a statistical method that helps make better guesses when information is missing. It takes what we already know and improves as we learn more. Sort of like when you are solving a puzzle and adding pieces creates a clearer picture. It’s a powerful way to make predictions in uncertain conditions, using prior knowledge as a starting point which is then updated with new data.

In the context of Carmen’s work, the Bayesian model was used to predict where lichen could be found on the landscape.

Building a map and model with Indigenous experts

The model was first created in 2006 by Dr. Scott McNay with input using a western approach to science, but Carmen often relied on her local Indigenous knowledge and the knowledge of community experts familiar with lichen habitats as a lever to support her research. Her community helped to provide key insights, including identifying areas that lichen often grow based on their experiences. These expert opinions were used to create ‘layers’ of data. Each layer represented an area of the landscape where lichen was likely to grow, similar to creating a heat map.

The overlapping layers in the model produced a visual map. Areas with higher potential for lichen presence show up in brighter colors, while areas with lower potential appear in duller shades. These highlighted areas were then the targets for field verification. Carmen would dispatch teams of Indigenous Guardians to these locations to confirm lichen density.

This work was not without challenges, however. Sometimes, upon visiting some of these high-potential areas, no lichen was found. “False positives,” Carmen explains.

Carmen’s team then had an opportunity to identify why these blips may have occurred. In some cases, an area identified for high potential might have been recently logged. In others, the model might have indicated a small area of high potential that turned out to be impractical for lichen pickers who needed larger areas.

Layers on layers on layers

Carmen’s research has helped peel back some of the complex mysteries and surprising ways of lichen. In some cases, Carmen found areas that the model predicted as low potential were abundant with lichen. Knowledge from Elders helped solve the mystery.

“The Elders from our community said it has to do with the forest and forest fires. So then what we did is we looked at Western science. And it did talk about some impacts of wildfires being beneficial,” she explains. “So, there was some knowledge I put in the thesis to say, ‘Hey! This is another lever, like another layer, you could put in the model.’ ”

“The Elders from our community said it has to do with the forest and forest fires. So then what we did is we looked at Western science. And it did talk about some impacts of wildfires being beneficial. So, there was some knowledge I put in the thesis to say, ‘Hey! This is another lever, like another layer, you could put in the model.’ ”

Carmen Richter, 2023 Sarah Baker Memorial Fund recipient

Model refinement and an adjustment period

Acknowledging these inaccuracies, the model was fine-tuned. Adjustments were made to account for these practical considerations and to correct the false positives. This fine-tuning incorporated new data into the model about the landscape found by Indigenous Guardians and the practicalities of lichen collection.

Two field seasons were dedicated to verifying the predictive models. Carmen worked alongside Indigenous Guardians to search for lichen and validate the locations against the model. This hands-on research contributed to the creation of an extensive map detailing lichen distribution.

Indigenous Guardians: A bridge between worlds

The Indigenous Guardians act as connectors — bridging the gap between traditional Indigenous knowledge and western science. Using tools like drones and GPS, these guardian programs help translate community wisdom into actionable data.

While out on the rugged landscape, their work wasn’t always easy. To authenticate the predictive model, they would often spend six hours a day, climbing to mountain tops and down deep valleys — sometimes, to empty lichen patches. Trekking out on the land into the most isolated parts of the wilderness, the Guardians braved the elements while finding lichen patches. Their role was a pivotal part in data collection.

The result was a new, updated map that predicted lichen locations with greater accuracy. This improved heat map serves as a more reliable guide for finding new areas rich in lichen.

This new map serves as an improvement from the original model originally published in 2006 while also incorporating the actual conditions and constraints of lichen pickers.

Strategic Mapping for Conservation and Indigenous Rights Advocacy

Carmen’s mapping has been a critical step in understanding which areas have been earmarked for different types of resource extraction and development. By pinpointing where these tenures coincide with vital lichen patches, she provides concrete data that can be used to inform land-use decisions by governments.

Now that critical lichen growth can be more accurately identified, overlapping interests such as forestry or mining licenses can be reviewed. By doing so, the project equips the community with the necessary data to advocate for these vital zones.

Carmen’s aim is to use this data proactively. She intends to facilitate communication between her nation and companies that hold land tenures, advocating for the protection of lichen-rich areas essential for caribou recovery.

By sharing her maps and findings with forestry stakeholders and other relevant parties, Carmen hopes to ensure that the presence of lichen is communicated and considered in all land-use planning. This would not only be an environmental conservation effort but also a step towards recognizing and respecting the sovereignty and rights of Indigenous peoples over their lands. Her research, therefore, serves a dual purpose: promoting caribou conservation and supporting the assertion of Indigenous rights in land management discussions.

Knowledge and research informs the Y2Y approach

The project doesn’t exist in isolation; it’s a crucial part of a broader conservation vision spanning the Yellowstone to Yukon region. Ensuring the well-being of the caribou and their lichen-rich habitats thus becomes part of a regional narrative — one that goes beyond the immediate community to inform conservation on a grand scale.

The project also showcases what can be achieved when community-driven imperatives mesh seamlessly with scientific rigor. It is a ground-up endeavor, initiated and sustained by a community that stands to gain the most from its success. In this way, every mapping exercise, every consultation with Elders, and every foray into the forests becomes a stitch in a cultural and scientific tapestry that binds people to their land and traditions.

In a big, busy world, the tiny unassuming lichen quietly shares a compelling story: one of community, resilience and of a future where both people and nature thrive.

The Sarah Baker Memorial Fund supports early-career researchers whose projects advance Y2Y’s conservation strategy and result in tangible benefits within the region. Sarah Jocelyn Baker’s appreciation for the natural world and ability to find solutions resonate with the aspirations and vision of Y2Y. We are honored to carry her spirit forward through the Sarah Baker Memorial Fund. Thanks to a gift from her extended family, Y2Y can offer grants to graduate students and postdoctoral fellows pursuing environmentally related studies in any post-secondary institution in Canada or the U.S.