What makes this species so special?

Y2Y’s Dr. Jodi Hilty shares a few thoughts on wolverines, including why she thinks they’re so special and what we can do to help these mysterious mammals:

In the early 2000s, I was overseeing a wolverine project with Wildlife Conservation Society in Grand Teton National Park where we had a live wolverine in a trap.

My colleagues prepared a tranquilizer jab stick and opened the log-cabin trap when the 35-pound (16 kg) wolverine erupted, sounding louder than a dinosaur, scattering people and equipment in every direction. That was the moment that I really became fascinated with wolverines.

A recent Grand Teton research project found fewer wolverines compared to previous counts. Are their numbers declining or is it a temporary blip? Hard to tell because they are such low density already and so elusive.

However, they are thought to be snow dependent, and sensitive to climate change. To the northwest, the headwaters of the Columbia River in British Columbia (B.C.) is predicted to be a climate refugia that could be an important stronghold for these wild creatures.

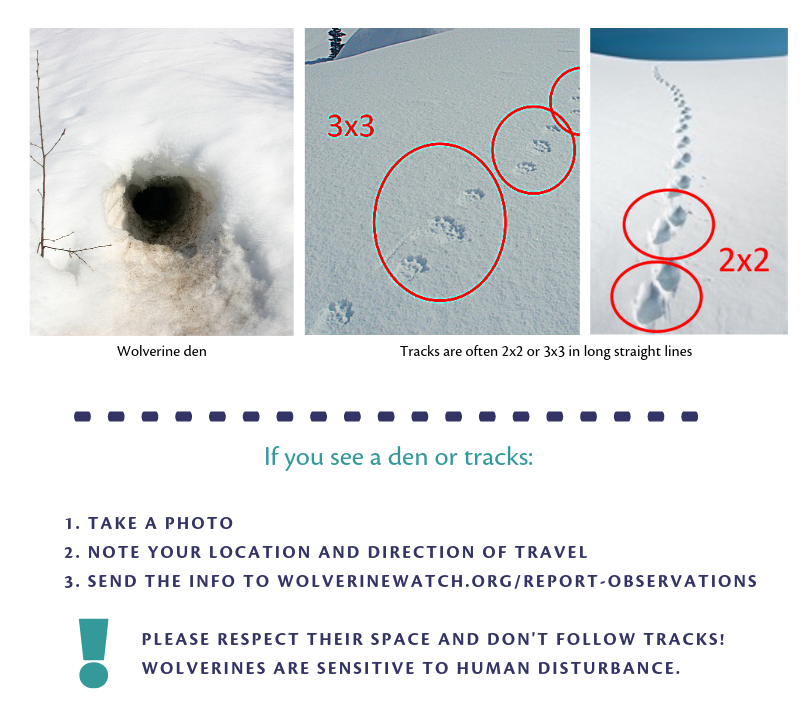

Wolverines rely on snow for many reasons, but especially to breed — females use deep snow to make their dens. They’re great moms, in fact, digging eight feet (2.5 meters) or more into the snow to provide warmth for their kits.

Born in February or March, the kits grow quickly, leaving dens in April or May before reaching full-grown size that same winter. But they stay by their fierce mother’s side and learn from her for two full years.

Wolverines sometimes seem like mythical beasts. Because they are so wily, wary and wide-ranging, they are rarely seen and their mystique often precedes them. But as we find out more about them thanks to brave researchers, we are beginning to understand how to help them succeed.

Fast (furry) facts:

- Researchers in B.C. and Idaho estimate there’s just one wolverine for up to 190 square miles (500 km2).

- They are the largest of the weasel family and have nothing to do with wolves!

- Wolverine coats consist of thick, dark, oily fur that is also frost-resistant.

- Their plate-sized furry paws act as snowshoes that prevent them from sinking deep into snow.

- Scientific name: Gulo gulo.

Partner projects that include wolverines:

Y2Y is supporting Mirjam Barrueto’s PhD work to learn how wolverines are doing in the Columbia Headwaters. Look out for Chasing a Trace, a film about her and wolverines, later this year.

How you can help:

We’re also partnering with Wolverine Watch. If you’re in the mountain ranges of southeastern B.C. and note tracks, a wolverine den or see a wolverine, report your findings.