Research signals a need for greater ongoing conservation efforts

Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y) announces research demonstrating that North America is home to the world’s most intact, least developed mountain system. This paper highlights that the 3,400 kilometer-long (2,100 miles) Yellowstone to Yukon “spine” of the Rocky Mountains is one of the few remaining connected mountainous habitats left on Earth. This research underscores the need to protect large, intact landscapes, including their diversity of ecosystems.

The findings are from a new research paper, Evaluating Ecosystem Protection and Fragmentation of the World’s Major Mountain Regions from lead author Dr. David Theobald of Conservation Planning Technologies.

Published in the June 2024 volume of Conservation Biology, the research significantly advances our understanding of conserving large landscapes while providing valuable insights into the current gaps in protecting nature, particularly mountains, which are critical for conserving biodiversity and ensuring human well-being.

“We have the opportunity, even the mandate, to ensure that the few places on the planet that are still wild today remain intact for future generations of people and wildlife,” says Dr. Jodi Hilty, co-author, president, and chief scientist of Y2Y.

Advancing better protections for mountain regions first requires societal awareness of how special places like Yellowstone to Yukon are. That enables and understanding that the best use of these increasingly rare wild places is to ensure that they are kept intact or in some cases even restored, says Hilty.

Many mountain regions are not well-protected, and the diversity of ecosystems within these areas are differentially protected as this research points out. Increasing protection for these mountains is an urgent need in a world dealing with the combined impacts of current land use and climate change on wildlife.

Large mountain regions like Yellowstone to Yukon, when intact, are global gems that enable species to move north, upslopes, and to different slopes and aspects, helping species adapt to a changing climate. Intact mountains also act like sponges, helping to store and regulate water release across large portions of continents through drier seasons. This type of research helps informs conservation planning and decision-making to address these impacts.

“Our research reveals that large mountainous regions have important differences in how much humans have changed and fragmented them, in addition to the degree to which they are protected,” says David Theobald, lead author. “Within each mountainous region, we need to safeguard those untouched ecosystems, focus protection on under-represented ecosystems, and connect ecosystems within mountainous regions for enduring conservation.”

About the report:

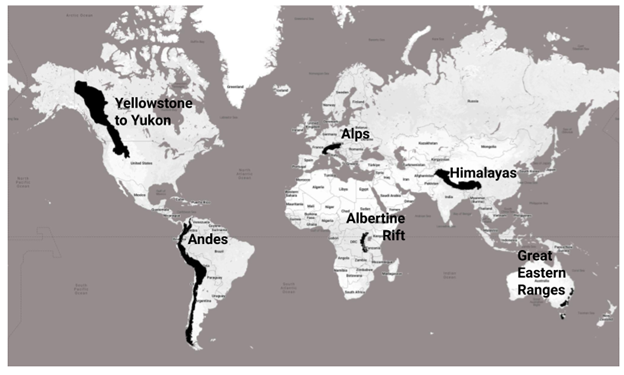

The six largest continuous mountainous regions on each continent outside of Antarctica, including Africa’s Albertine Rift, Europe’s Alps, South America’s Andes, Australia’s Great Eastern Ranges, Asia’s Himalayas, and the Yellowstone to Yukon region in North America’s Rockies were studied.

Of the six study areas, the Yellowstone to Yukon region stands out with the lowest levels of human changes and the highest levels of intact, or “wild” landscapes, with minimal fragmentation (or loss due to human-based changes). Yet, at 15.6 percent protected, while greater than the US and Canadian average of 12 percent, the region is short of the Global Biodiversity Framework goal to protect 30 percent of the world by 2023 as part of its effort to protect the amount of wilderness required to stem the loss of biodiversity.

Other key findings:

- Mountains are often thought to be less impacted by people and to contain more protected areas. However, this research shows that about half of the mountain lands studied have been impacted by human activities, which matches the global average.

- Fragmentation has degraded the ecological integrity of some mountain ecosystems by up to 40 percent.

- Only two of the six mountainous regions studied meet the 30×30 protection standards / Global Biodiversity Framework goal of protecting 30 percent of the world by 2030.

“This research shows that the Yellowstone to Yukon region is a global gem and that Canada and the U.S. should prioritize protecting it,” adds Hilty. “For more than 30 years, we’ve been working with several hundred partners to connect and protect this region. Would it be fantastic if this gem were prioritized to achieve the 30 percent protection that communities in the area have already requested? We have made immense progress together and have more to go. Our mandate is to ensure this stronghold stays resilient in the decades to come.”

Furthermore, the research also tells us that when we carefully measure the health of the ecosystem and the extent to which human activities affect it, we can determine how well we meet conservation goals.

“Essentially, this work provides us with a clearer global picture and more information to make better decisions for conserving mountain ecosystems,” says Theobald.