From mother grizzly bears and their cubs, to herds of elk, to a family on a summer road trip to a favorite picnic spot: we are all trying to get where we’re going safely.

For wildlife, our roads have become dangerous, even deadly, barriers that cut through their habitat and fragment it, cutting them off from the resources they need to survive.

Enter wildlife crossings: one of conservation’s greatest success stories.

What are wildlife crossings?

Wildlife crossings are specially designed structures that allow animals to safely cross roads, highways, and railways.

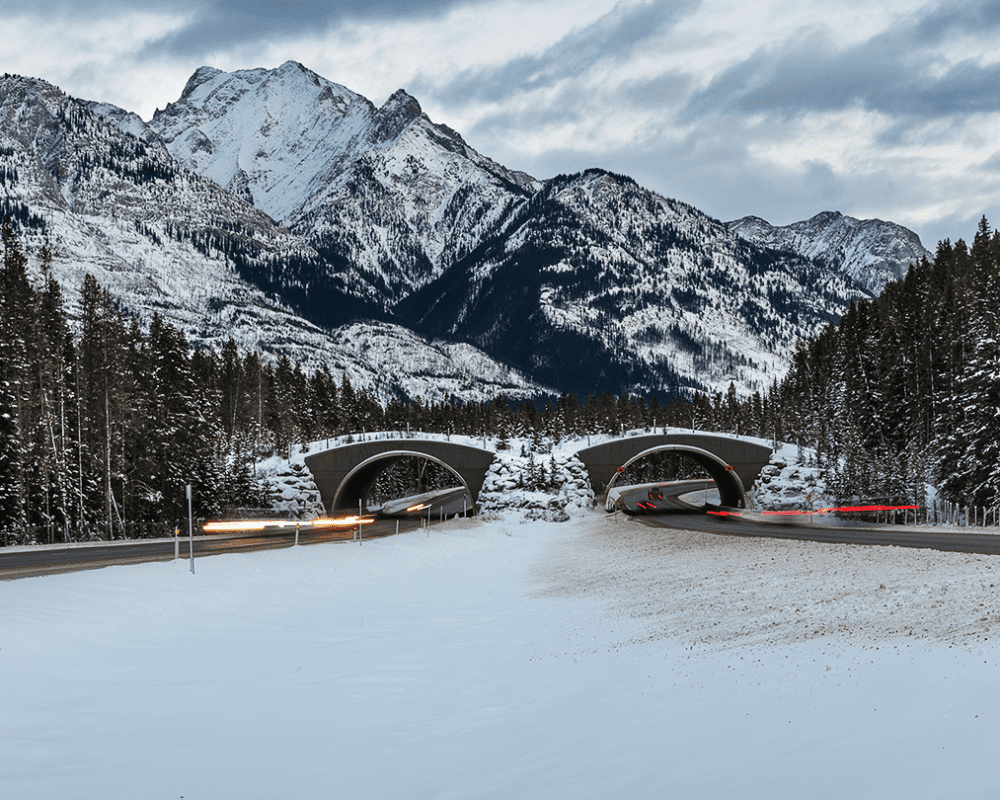

While most people are likely to think first of the bridges arching over highways, crossings come in two types: overpasses that bridge over roadways, and underpasses that tunnel beneath them.

These aren’t just random bridges and tunnels, though. They’re carefully engineered with wildlife behavior in mind, and based on information about where wildlife cross from years of research and local knowledge.

Overpasses are landscaped with native soil, plants, and trees that allow them to feel and look like the surrounding habitat. They’re typically wide, open, and short — perfect for species like grizzly bears, elk, and moose who prefer to see where they’re going.

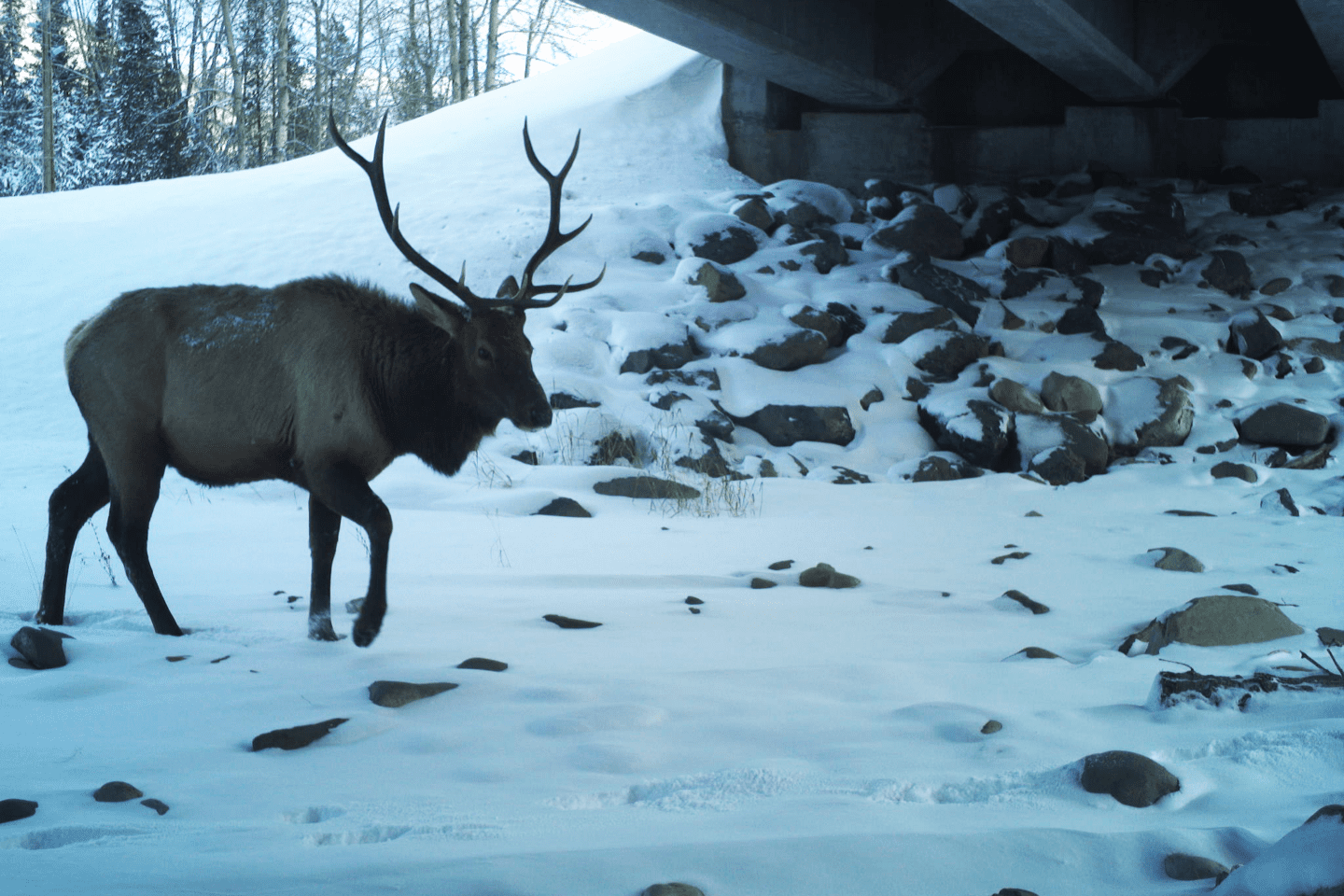

Underpasses, on the other hand, are lower and darker, providing the cover that species such as cougars and black bears instinctively seek.

The secret ingredient? Fencing.

Wildlife fencing runs along both sides of the highway, guiding animals toward the crossings and preventing them from wandering onto the road. This guide keeps wildlife off the busy, dangerous roads, funneling them to safety.

Why do we need wildlife crossings?

Roads are among the biggest human-created barriers to wildlife movement. Animals don’t recognize property lines or highway boundaries. They simply follow migration routes and seasonal patterns that have guided their species for millennia.

When we build roads through their habitat, we create a potentially fatal obstacle course.

The consequences go beyond tragic roadkill. When animal populations become isolated by highways, they lose access to mates, food sources, and diverse genetic pools.

Species such as grizzly bears and wolverines, which have large home ranges and low reproduction rates, are particularly vulnerable. Without connections between populations, genetic diversity suffers, and small isolated groups face declining numbers and potential extinction.

For humans, the dangers are equally real. Wildlife-vehicle collisions cause injuries, fatalities, and millions of dollars in vehicle damage each year. Anyone who regularly drives through wildlife country has likely experienced the heart-stopping moment when an animal appears in their headlights.

Do wildlife crossings work?

Absolutely. The proof is overwhelming.

In Banff National Park, home to the world’s longest-running wildlife crossing research program, cameras have documented more than 250,000 wildlife crossings since monitoring began.

The system of 44 structures and fencing along 82 kilometers of the Trans-Canada Highway has reduced wildlife-vehicle collisions by more than 80 percent overall, and by an astounding 96 percent for elk and deer specifically.

Research shows animals quickly learn to use these structures. Elk were famously the first to catch on, sometimes using overpasses even while they were under construction. More cautious species like wolves and grizzly bears may take up to five years before they feel comfortable, but eventually they do.

A Montana study found animals were 146 percent more likely to use crossings than to attempt crossing at random locations.

Across the Yellowstone to Yukon region there are 204 wildlife under- and overpasses with fencing. These crossings help species as large as grizzly bears and elk and as small as Western toads and salamanders cross safely, creating success stories not just for wildlife, but for safer roads for people, too. Many of these were established with help by Y2Y or by partners.

These infrastructure improvements are reducing vehicle-animal collisions, restoring habitat connectivity, and promoting genetic diversity.

How much do they cost?

Wildlife crossings require significant upfront investment, with costs varying widely based on size, location, and terrain.

However, research consistently shows these structures often pay for themselves within 10 years or less through reduced collisions, lower insurance claims, decreased emergency response costs, and less property damage.

More importantly, studies have found that the societal costs of doing nothing often exceed the expense of building crossing structures. When you factor in improved wildlife viewing and hunting opportunities, safer travel, and thriving animal populations, wildlife crossings emerge as infrastructure investments that benefit both people and nature.

Crossings into the future

While wildlife crossings work remarkably well, they remain relatively rare due to cost and the challenge of retrofitting existing highways.

Conservation organizations like Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative focus on the most critical connectivity hotspots — places where roads sever vital links between wildlife populations.

The ideal solution is to limit road-building and keep wildlife and nature in mind when designing infrastructure when possible. But where highways already cut through habitat, wildlife crossings offer a proven way to heal the fractures we’ve created, reconnecting landscapes and giving both animals and people a safer path forward.