Master’s student adds to cross-border knowledge of ‘ecosystem services’ in Yellowstone to Yukon region

Nature doesn’t need to account for borders to work the way it always has.

Forests, freshwater, wild lands, plants and animals flow, grow, move and stretch across the “lines” humans have created. Along the way, people also benefit from these natural (and often highly sensitive) resources. When we take care of nature, it can better take care of us.

Knowing how we benefit from healthy ecosystems can help us to better protect them.

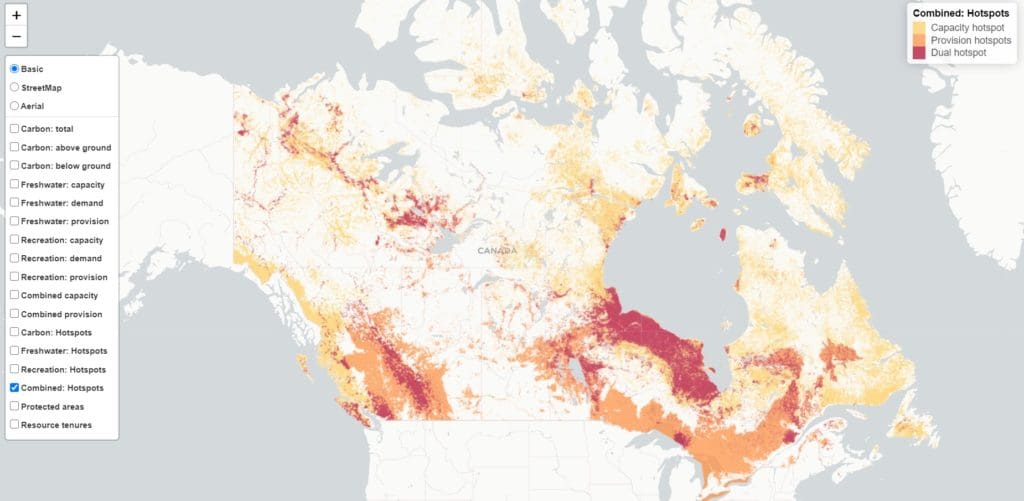

In 2020, a team of scientists, including from Y2Y, developed new methods to study where key “ecosystem services” — carbon storage, freshwater provision, and nature-based recreation — are most abundant in Canada and where they are in most demand by people.

The 2021 research paper showed that several of the most important hotspots for all three benefits are on the “Canadian side” of the Yellowstone to Yukon region are in Alberta’s Eastern Slopes and the Upper Columbia region of British Columbia.

We also wanted to know about the same ecosystem services on the “U.S. side” of the Yellowstone to Yukon region. Over eight weeks in 2021, Stephanie Rockwood, a master’s student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison collaborated with lead author of the ecosystem services paper, University of British Columbia’s Dr. Matthew Mitchell, and conservation scientist Dr. Aerin Jacob, a co-author on the paper, to investigate it.

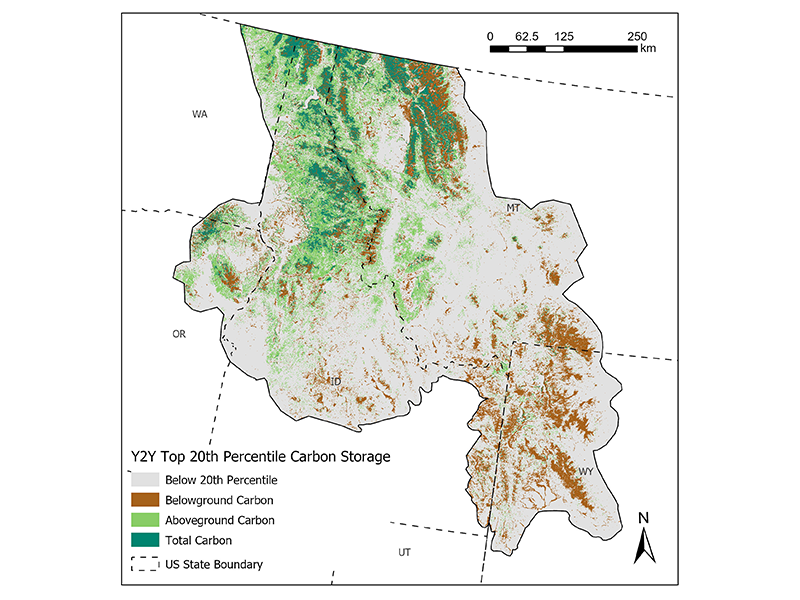

More specifically, Stephanie evaluated U.S. and global datasets and how to apply methods from the Canadian research across the United States. This was a big undertaking! We are delighted that she was able to complete all steps to map and model carbon storage both above- and below-ground as well as sketch out the next steps for water provision and recreation.

Carbon considerations in the Yellowstone to Yukon region and beyond

From living and dead trees to the soil that nourishes them, we need to consider where carbon is stored above and below-ground, and how land management practices (such as logging) impact the sequestration and storage of carbon.

Carbon storage is an important ecological function for mitigating climate change. The decisions we make now about how to manage land impact the future of the earth’s climate.

“Research projects like Stephanie’s are important for Y2Y’s U.S. program,” says Hannah Rasker, Y2Y’s U.S. program and adaptive management co-ordinator. “Information like this — knowing where and how much carbon is stored both above and below ground — helps us prioritize conservation efforts and focus our impact.”

The more ways we can demonstrate how nature and people are interconnected, the better. Stephanie says this interconnectedness stood out during her analysis.

“Information like this — knowing where and how much carbon is stored both above and below ground — helps us prioritize conservation efforts and focus our impact.”

Hannah Rasker, Y2Y U.S. program and adaptive management co-ordinator

“A river carrying freshwater for millions of people keeps flowing beyond international borders,” says Stephanie. “If you look at the Yellowstone to Yukon region as a whole, you’ll see that much of it is connected. It’s important that we keep it that way.”

Stephanie also embraces a natural interest in how each part of nature is connected across landscapes through her past work in plant ecology with the National Park Service.

“Learning about how different parts of the landscape are connected spatially combines my naturalist interests in learning about a place, plants, and animals, and the power of data in communicating these relationships visually,” explains Stephanie, referring to the use of geospatial information in this project.

In fact, this interest in connecting information to place is what guided Stephanie to where she is in her career now.

“It’s one way to connect to the land a little more, and being able to communicate that — using a map, chart or other interactive tool — can also help others connect to the places they live and play.”