New research looks at how we can best manage moose and conserve endangered southern mountain caribou in southeastern British Columbia

In the Revelstoke region of southeastern British Columbia (B.C.) the snow is deep and the landscapes are rugged. The rare inland temperate rainforest found here is mysterious, and the valley’s hills are cloaked with ancient hemlock and cedar trees.

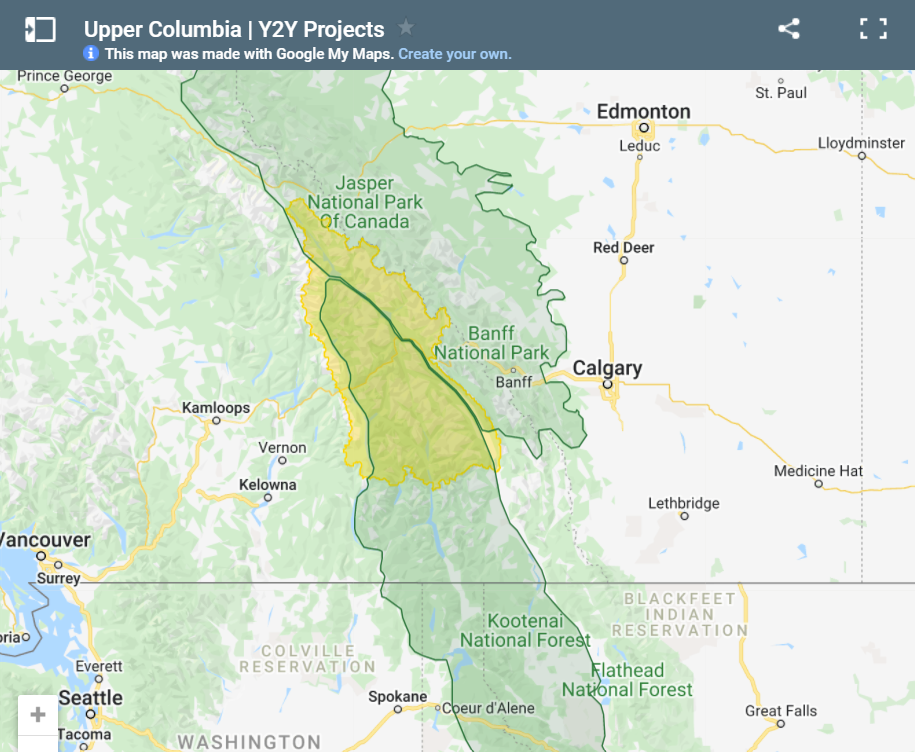

These are a few reasons Mateen Hessami — master’s student at the University of British Columbia-Okanagan (UBCO) and 2019 recipient of Y2Y’s Sarah Baker grant — is drawn to this part of the incredible Upper Columbia region, which is also an important climate refugia.

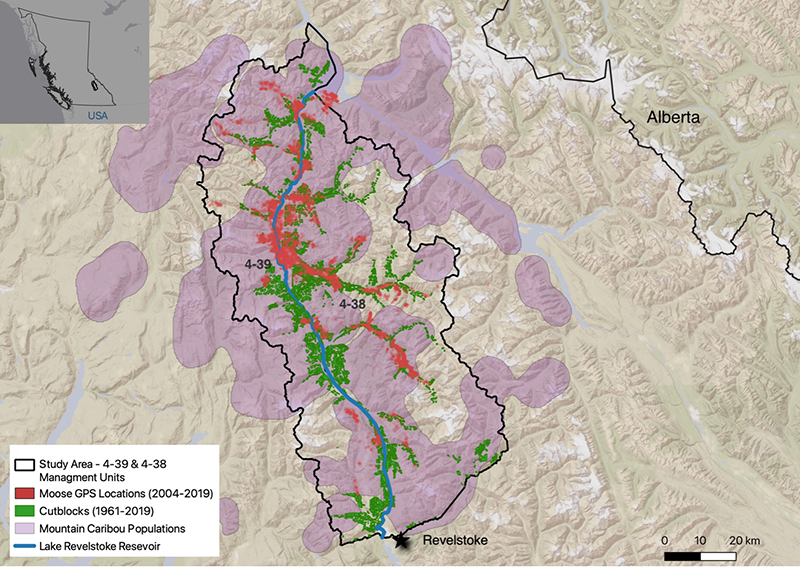

Mateen has focused his master’s research in the mountains north of Revelstoke, seeking to understand moose ecology and hunter harvest dynamics and the implications for caribou conservation and local First Nations.

‘Moose factories’ and wildlife management methods

The Columbia North caribou herd found in the Upper Columbia region near Revelstoke shows some potential for recovery, with close to 200 animals and a small increasing population trend. With recent extirpation (i.e., local extinction) of caribou herds just across the border in the United States, it is also one of the southernmost herds in North America that remains.

Mateen’s research asks: How can we best manage moose but still conserve the Columbia North herd of endangered southern mountain caribou?

The answer is complex, yet critical for caribou recovery goals, restoring landscapes, and improving connections among people and the land.

Ecosystems are made up of living organisms, the physical environment, and all their interrelationships. Those relationships mean that when one part of the ecosystem changes, other parts of the system can also be affected. People are also part of these systems.

Human activity and development have brought about enormous changes in the Revelstoke area. More than a century of industrial logging, dams, and mining (and related roads) mean habitat loss, fragmentation and degradation. Today, increasing tourism and more people recreating in this area than ever before can inadvertently mean wildlife disturbance, displacement and stress.

A complex relationship

Wildlife is challenged with finding places to live and ways to move about the landscape.

Cutblock logging practices have also increased the extent of young forests in the Revelstoke region. With a penchant for plants found in less mature forests, moose moved in and grew in numbers. As a result, their main predators, wolves, also saw a population increase.

The dilemma? Southern mountain caribou is an endangered species in Canada that also live in this area. Wolves also hunt this species. So an increase in moose numbers indirectly, and negatively, affects caribou.

In 2003, the B.C. government distributed more moose tags than usual to non-Indigenous hunters to try to manage the situation. At first, this contributed to the decrease in moose numbers from around 1,600 in 2003 to around 600 moose in 2007.

However, Mateen’s research shows that over the years that followed, an unexpected phenomenon took place in how the moose population responded to increased hunting.

Fewer moose on the landscape meant more resources (i.e., food) were available, which meant that the remaining moose calves had less competition and better survival than before.

“Over time, the reduction and stabilization of moose populations carried out by hunters has, in a sense, created a ‘moose factory’ with more and more young moose surviving,” says Mateen. “Our research shows one of the best strategies to strike more balance for endangered mountain caribou recovery, and people that rely on moose, is to reduce and stabilize moose numbers at an ideal level.”

Having a lower and more stable moose population means that predator numbers are more likely to represent historic conditions. In turn, that means better chances of recovering caribou when combined with other conservation strategies such as habitat protection and restoration.

“Our research shows one of the best strategies to strike more balance for endangered mountain caribou recovery, and people that rely on moose, is to reduce and stabilize moose numbers at an ideal level.”

Mateen Hessami, UBCO master’s student and Y2Y Sarah Baker grant recipient

Mateen’s research also showed that moose prefer cutblocks of forests 10 to 30-years-old. Knowing the specific forest age and type that moose select or avoid can help wildlife managers forecast moose populations and balance the food-security needs of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people that rely on moose — while also recovering endangered caribou populations.

Maintaining stable wildlife populations will require careful management and stewardship. However, Mateen emphasizes that Indigenous Peoples have stewarded and managed food webs for thousands of years, just at different scales.

Weaving Indigenous-led policy with western science to recover caribou

Learning the polices and barriers to reconciliation among Indigenous and non-Indigenous governments in Canada has been at the center of Mateen’s research.

Now that his Master’s research is finished, Mateen is working to better understand how moose reduction and stabilization has affected nearby First Nations. One example is the Splatsin Indian Band, who were marginalized in the decades-long effort to manage moose populations.

“It’s been really important to listen to and learn from the Indigenous Peoples who have knowledge and perspectives about the Revelstoke Valley,” says Mateen, who is now working for Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute’s Caribou Monitoring Unit and supporting the Splatsin Indian Band in their quest to become regional leaders in caribou recovery.

Caribou recovery will continue to be a central conservation issue in Canada. However, Mateen adds that understanding the implications of wildlife management, such as stabilizing moose populations, while fulfilling cultural, food and economic needs of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people is a significant knowledge gap in Canada.

Protecting ecosystems, the importance of science and collaboration, and a healthy future for people and wildlife are central to Mateen’s research as well as to Y2Y’s mission and vision.

While completing his master’s research, Mateen helped lead a research effort to revise and “Indigenize” the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, the prevailing model for how wildlife is managed in Canada and the United States.

Mateen worked with his academic supervisor, Dr. Adam Ford, and other UBCO and University of Guelph researchers to weave critical Indigenous-led policies and worldviews into the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation in a 2021 peer-reviewed research paper published in FACETS.

“It’s a great model, but was majorly lacking in Indigenous histories, perspectives and knowledge systems,” says Mateen. “Reconciliation among provincial, federal and First Nations governments is a key process to improving wildlife conservation strategies in Canada.”

What does this mean for the Yellowstone to Yukon region?

Protecting ecosystems, the importance of science and collaboration, and a healthy future for people and wildlife are central to Mateen’s research as well as to Y2Y’s mission and vision.

“I am both humbled and honored to have been chosen for the Sarah Baker Memorial Fund award,” says Mateen. “I am keen to continue working with Y2Y to advance science and policy initiatives that safeguard wildlife and ecosystems for future generations.”

Y2Y and its partners continue to be an important part of this kind of work both in the Upper Columbia and other parts of the Yellowstone to Yukon region.

“The Upper Columbia is an incredibly special place with people who care deeply for it and wild species and spaces unique on the planet,” says Nadine Raynolds, Y2Y’s Upper Columbia program manager. “It is wonderful that researchers, residents, conservation organizations, governments and Indigenous Peoples are working together to discuss and explore the best actions so that this region will thrive well into the future.”

Learn more about Mateen’s research in this March 2020 article.

The Sarah Baker Memorial Fund supports science by early-career researchers that advance Y2Y’s conservation strategy and result in tangible benefits within the region. Sarah Jocelyn Baker’s appreciation for the natural world and ability to find solutions resonate with the aspirations and vision of Y2Y. We are honored to carry her spirit forward through the Sarah Baker Memorial Fund. Thanks to a gift from her extended family, Y2Y can offer grants to post-secondary students and postdoctoral fellows pursuing environmentally related studies at post-secondary institutions in Canada or the United States.