Do human actions affect how female wolverines move and reproduce? Y2Y partner Wolverine Watch gives the latest look into a multi-year study that helps answer this question and more.

Deep, high up and across Alberta’s central Rocky Mountains, and into the seasonally snow-packed ecosystems of southeastern British Columbia, there is a wild species expert in evading the human eye. These animals travel far and wide across high elevations and harsh landscapes.

That’s right, we’re talking about wolverines!

Wolverines are elusive and very sensitive to human activity, making them more challenging to study than some other species in the Yellowstone to Yukon region. Luckily, there is an all-star team of researchers called Wolverine Watch, dedicated to studying the wolverine’s unique behavior and ecology.

Why is so much emphasis put on this one kind of animal, you ask? Wolverines are at risk; in fact, they’re listed as ‘Special Concern’ under Canada’s federal Species at Risk Act because of declining populations in the southern part of their range. They are also considered either ‘imperiled’ or ‘vulnerable’ in the U.S. portion of the Yellowstone to Yukon region.

“Wolverine are a quintessential Y2Y species: individuals need a lot of room to roam and populations need connected landscapes to thrive.”

Dr. Aerin Jacob, Y2Y conservation scientist

Like many other species in B.C. and Alberta, wolverine habitat is becoming increasingly broken up and altered.

Recent research shows concerning results on wolverine numbers even inside the “largest contiguous protected area in southern Canada” — Banff, Yoho and Kootenay national parks — likely due to a combination of human activity in and surrounding parks, including habitat loss, as well as trapping for fur.

Wolverines also reproduce slowly and require vast, secure areas to roam so they can maintain thriving populations.

That’s why Y2Y is proud to partner on a multi-year research project on wolverine populations, reproduction and connectivity in B.C.’s Upper Columbia region and in Alberta’s central Rocky Mountains.

The more we understand about wolverines and how our actions impact them, the more we know what’s needed to keep them connected and protected. Your support of Y2Y helps make that happen.

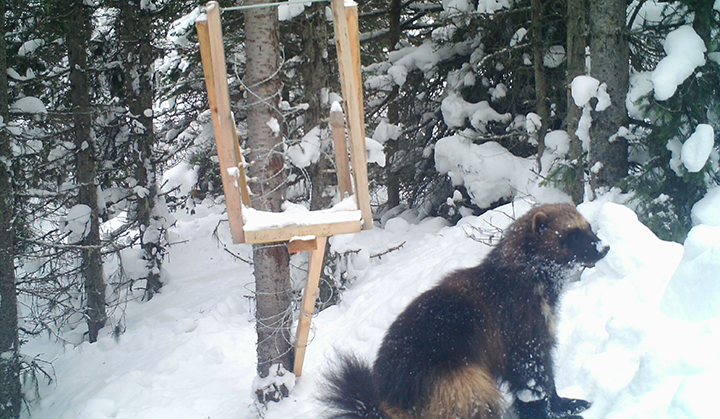

Mirjam Barrueto, a researcher with Wolverine Watch, leads this research across a massive study area (19,305 square miles, or 50,000 square kilometers, to be specific!) Her research takes a non-invasive approach using methods like hair snags, remote camera footage, and community science.

In this post, we’ll dive into some of the research highlights from 2020 — but first, let’s get to know Mirjam.

Mirjam Barrueto: the bad-ass scientist on a quest to find breeding female wolverines in the high alpine mountains of Canada’s west

Mirjam Barrueto’s research career took off in 2011 when she began working with Dr. Tony Clevenger to study the interactions between wildlife and roads in and around Banff National Park. Tony’s projects included a field study to find out whether wolverines cross the Trans-Canada Highway, and soon Mirjam’s work started to take an unexpected, sharpened focus on wolverines.

In 2017, she joined Dr. Marco Musiani’s research group at the University of Calgary as a PhD student to study female wolverines and their interactions with human activities, with academic guidance from researchers including Y2Y’s conservation scientist, Dr. Aerin Jacob.

“Wolverine are a quintessential Y2Y species: individuals need a lot of room to roam and populations need connected landscapes to thrive. And studying wolverines is tough!” says Aerin. “It’s great to work with Mirjam and her dedicated team on this big, wild topic.”

Mirjam teamed up with filmmaker Leanne Allison in 2019 to document aspects of her research on female wolverines in the film Chasing a Trace. The film was funded through a TELUS Storyhive grant, and was selected by the Banff Centre Mountain Film and Book Festival.

“The thing I admire most about wolverines is how fast they can go, and how they are always on the move; that they are patrolling their massive territory, going over mountains, rocks, ice,” Mirjam describes in the film. “Then, they find some frozen bone to eat and they just keep running.”

Mirjam was also recently named one of 2021’s Wilburforce Leaders in Conservation Science — a program to develop and activate a strong network of scientists across western North America with the readiness and vision to be leaders.

Results from Wolverine Watch’s 2020 annual report

We’re not exaggerating when we say this was a large-scale research project! It took three years for Mirjam and her team, including her collaborator Anne Forshner at Parks Canada, to collect data on wolverine reproduction and movement in their study areas — and they might do more fieldwork next year.

It wasn’t until 2020 that they started to bring together all of the data and figure out how it could help with wolverine conservation.

Here are some highlights from the latest annual report:

In 2020, the research team gathered important information on wolverines through 127 data collection stations.

Over the first three years of this project, they captured millions of photos of wolverines and friends…

…and thousands of hair samples for DNA analysis.

Estimating the wolverine population density and how they are dispersed on the landscape will be determined by looking closer at both the photos and DNA results in the coming year.

Early results from the photos show there could be up to 199 individual wolverines in the study area. That includes 56 males, 86 females, and 57 of undetermined sex. Forty-six of those females appeared to be breeding in at least one of the years.

Several long-distance movements of individual wolverines were also detected between or within years. A male wolverine made the longest travels in 2015 in the southern Purcell mountains, and later detections between 2018 to 2020 in the Selkirk mountains east of Revelstoke, B.C.

For species that rely on these kinds of long-distance movements to find their own territory and reproduce, it’s crucial they can travel through the landscape without too many barriers, such as highways.

Previous research showed that busy roads can impede wolverine movements — especially females, who usually stay on the side of the highway where they were born. Knowing how and where wolverines move, and collecting genetic information about them, can help to identify barriers that limit the movement and reproduction of wolverines.

Ultimately, this helps to better understand what places are most important to maintain and restore connected wolverine populations.

A good chunk of Wolverine Watch’s research is also fueled by the people who are most likely to use the same landscapes as wolverines, such as backcountry recreationists, guides and others who make a living in these places.

Through community science, researchers gather important data through reports of wolverine sightings and signs, like tracks and dens.

What’s next?

Mirjam and her team at Wolverine Watch are taking what they learned in the field to analyze, summarize and share information. They are working to refine population estimates and incorporate landscape variables and human activities (like forests, logging, roads, and dams) to understand how we can help wolverine thrive in these areas over the long-term.

“In 2016 I initiated the project that now, since 2017 is my PhD research project,” Mirjam explained in her Wilburforce Leaders in Conservation Science bio. “Somehow, I managed to inspire a diverse group of people to collaborate on landscape-scale wolverine research, enabling me to develop, fund and complete the data collection and genetics, and begin the data analysis portion of my PhD.”

Because wolverines have such big home ranges — up to 1,000 square km in some cases — and research has found low abundance even in big protected areas, it’s important that conservation science, practice and policy considers them at the ‘large landscape’ scale. That means monitoring them across borders and protecting and managing large areas in integrated, holistic ways.

We couldn’t be part of this crucial work without your support of Y2Y’s mission. For this and other wolverine-related projects, you donated, showed up to local events, shared information about wolverines on social media, attended our Wildlife Wise workshops, and contacted decision-makers about wolverine conservation.

You love wolverines, and it shows!

Proud partner: More about Wolverine Watch

Wolverine Watch is a group of researchers who collaborate on wolverine related scientific projects. Their research methods are non-invasive, made possible by using remote cameras, drones and DNA analysis of hair samples.

They focus on landscape-scale questions of wolverine ecology in multi-use landscapes — inside and outside protected areas, places with recreation, forestry, and other activities. This work aims to provide science-based information to agency decision-makers, First Nations, landowners, natural resource extraction and recreation/tourism industry, recreationists, and non-profit groups so that the needs of wolverine are incorporated into land use plans, species management plans, highway mitigation and other projects.

Along with Mirjam’s important work, Y2Y also partners with Wolverine Watch researchers Doris Hausleitner and Andrea Kortello as they work to identify den sites in the Selkirk and Purcell mountain ranges. Through their research and community science reporting, they’re learning what’s needed to manage and conserve wolverine habitat in those areas.

This research is supported in part by funding from Mitacs Canada and The Volgenau Foundation.

More information, reading and resources:

- Read more about keeping wolverines connected

- View and share our ‘Wildlife Wise’ winter recreation tips for sharing space with species like wolverine and caribou

- Watch this video about wolverine habitat and movement in B.C.’s Upper Columbia region

- Effects of human and natural habitat factors on wolverine density and connectivity [PDF Report]