Grizzly bears appear in Y2Y’s logo and many of the photos we use. But beyond being big, beautiful symbols of wild places, did you know there are scientific reasons parts of our work centers on them?

It’s true, and it’s because grizzly bears are considered an “umbrella” species. Many conservation efforts around the world focus on umbrella species, which goes beyond helping individual species to effectively conserving whole ecosystems.

What is an umbrella species?

Since the term was coined in 1984, focusing efforts on umbrella species has become an increasingly common part of conservation strategies.

Generally, it refers to situations when protecting what a single species needs also protects multiple nearby species (and those further down the food chain) that share the same habitats or ecosystems. When Y2Y works to conserve grizzly bears, we help conserve all species that “fit under their umbrella”.

Similar to a mother duck sheltering her ducklings under her wings in a rainstorm, umbrella species can shelter other species who use the same space.

Umbrella species often have large home ranges and need to use multiple habitats within a year, so they overlap (or “co-occur” to scientists) with many other species in the same landscape.

Ensuring that umbrella species have what they need to survive benefits other (often overlooked) species with smaller individual home ranges or more specific habitat needs, such as amphibians and rodents.

An additional benefit is that umbrella species tend to be very charismatic. Grizzly bears are widely recognized as “charismatic megafauna”, which is a fancy way of saying that they’re big animals that people love. That can make it easier to generate public interest and build support for their protection.

What makes Rocky Mountain grizzly bears special?

We often think of grizzly bears as mountain animals, but these large omnivores used to live all the way across the Great Plains.

Their massive shoulder hump and long claws help them to dig and many of their behavioral instincts reflect life in open or semi-open areas.

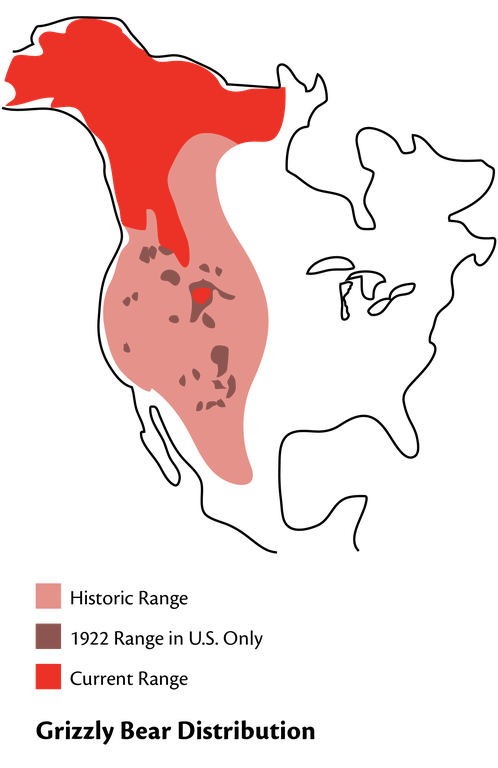

In fact, as a highly adaptable species, grizzly bears once lived in most parts of western North America, ranging from Mexico to the Arctic circle, and from the west coast across the Prairies.

Currently, these omnivores only roam two percent of their original range in the contiguous U.S., mostly in isolated “islands” of habitat.

Rocky Mountain grizzly bears are on the front lines of grizzly bear distribution throughout North America.

What happens to grizzly bears in the Rocky Mountains is important for grizzly bears across the continent, to prevent further range shrinkage.

Why are grizzly bears good umbrella species?

One part of being an effective umbrella species is a large home range. Grizzly bears are often on the move looking for places to feed and breed.

They need to use many different habitats in any single year and can thrive everywhere from valley bottoms and grasslands to high alpine meadows and forested areas.

The average home range of an Alberta Rocky Mountain grizzly bear is 100 to 300 square kilometers. Within these large home ranges, grizzly bears face a variety of threats and need large tracts of intact, connected land to thrive.

The Rocky Mountains are also relatively sparse in grizzly bear foods compared to other places that grizzlies live (like the west coast), which means that bears must travel large distances to meet their nutritional needs.

As charismatic megafauna, grizzly bears also attract attention and capture people’s admiration and interest. In addition to their large home ranges and varied seasonal food requirements, their need to travel to avoid people in landscapes dominated by humans and development, and the way they captivate the imaginations of millions of people make them good focus for conservation, creating positive outcomes for other species.

Research in the Canadian Rockies shows that at least 16 other large and medium-sized mammals such as lynx, wolves, bighorn sheep and deer, also benefit from the role of grizzlies as an umbrella species.

The details depend on the spatial scale considered (e.g., local or regional) but other beneficiaries of grizzly bears as an umbrella species can also include plants and flowers, fish, songbirds and even insects.

Why are grizzly bears important for a healthy ecosystem?

Sometimes grizzly bears are called nature’s rototiller. Often they unearth roots and tubers in meadows or dig up huge areas in search of crafty ground squirrels or marmots.

Where grizzlies overlap with salmon on the west side of the Rockies, bears feed on migratory fish and inadvertently distribute much-needed nutrients via fish carcasses or bear feces throughout the nearby forest. In the fall, one bear can consume 250,000 berries daily. Each of those seeds are distributed across the landscape in bear feces, making grizzly bears expert planters of their future food source.

Grizzly bears have seasonal home ranges that change from spring to summer to fall. Their home ranges can vary in size depending on how plentiful food resources are and how far they have to travel to meet their nutritional requirements.

Whether it is an alpine meadow or gravel bed river, the places grizzly bears live are also home to many other species. Generally, if grizzly bears have the resources that they need to thrive, many other species that live in the same habitats and have some of the same needs will thrive too.

What about keystone, flagship, indicator or focal species?

Other terms are sometimes used when it comes to wildlife ecology and conservation. Some are similar to umbrella species, but others are quite different, and not all are interchangeable. They are all types of the broader term “surrogate” species, which are species or taxa that are representative of multiple species or aspects of the environment.

Keystone

Keystone species play an essential role in the structure, function and/or productivity of a habitat or ecosystem. They have effects on many other species in an ecosystem that far outweigh their size or abundance, comparatively.

The name keystone comes from a specially shaped block used to build stone arches. Removing the keystone will make the arch collapse. So, like keystones, if these species disappear, they can seriously impact ecosystems, even causing a collapse.

In the Yellowstone to Yukon region, one example is beavers. This is thanks to the essential role they play in habitat function, particularly related to engineering ponds and wetlands.

Another example that was surprising for scientists to learn was the importance of wolves in Yellowstone. When wolves were reintroduced, they hunted and ate elk. This allowed aspen to grow, giving beavers trees to make dams, which impacted the water levels in the entire ecosystems.

Keystone species presence or activities also support a large number of other species in the community and can also often be good umbrella species.

Flagship

Flagship species are usually large, highly recognizable symbols of a specific region, environmental issue or cause. These species are often the “face” of a campaign or ambassadors, used in marketing conservation efforts.

Grizzly bears are also flagships, but other examples in the Yellowstone to Yukon region are mountain caribou and wolverine.

Flagship species are more of a public communication conservation tool and aren’t necessarily tied to keystone, umbrella, or indicator species which are more scientific terms. Like those overlapping with umbrella species, often those who share habitat with flagship species benefit from conservation or increased focus on these species, too.

Indicator

Indicator species often show — or indicate — the health of, or a certain process in, an ecosystem. Indicator species are usually the first sign that something is out of balance. This is similar to “canaries in the coalmine” that were used to let miners know when the air was becoming toxic.

In the Yellowstone to Yukon region, bull trout are often considered indicators for quality of the headwaters of Rocky Mountain rivers. This is because they have specific habitat needs, only spawning in very cold, clear freshwater rivers and are sensitive to even slight changes. If trout populations are declining, then the water quality is also declining.

Focal

Focal species is a general term that means one, or sometimes more, species that is the focus of conservation action. Multiple focal species can comprise a set of targets used in conservation planning, instead of one single species. They can include species with specific sensitivity or habitat requirements, whose distributions and numbers are well known, or otherwise need attention.

Umbrella species are not the only tool

Y2Y’s focus on grizzly bears as an umbrella species helps target our work and conservation efforts and decision-making across this large landscape. However, it is not the only tool we use when it comes to conservation planning, advocacy, or on-the-ground work.

Umbrella species are not the cure-all to conservation challenges. While decisions can positively impact species and the place they live, there are limitations. This is why grizzly bears are not the only factor in Y2Y’s scientific recommendations to governments or other decision-makers.

What are we missing?

There is some criticism around the umbrella species concept, or particular umbrella species. Focusing conservation decisions only on carnivores such as grizzly bears can miss other species, including some at risk of extinction.

For instance, research from the U.S. northern Rockies shows this is because grizzly bears are not always closely linked to low elevation and non-forest habitats. These are most at risk of habitat loss and fragmentation by human development. And in British Columbia, research shows that it might be best to use a combination of hunted- and non-hunted species in broad-scale conservation efforts.

Also, because carnivores can have different, specific needs, they may not always be good umbrellas for fish, insects or plants — others species that are important.

Ultimately, research and context-specific information can help to determine the best strategy or strategies for place-based conservation. A multi-species approach is often best because no single one can cover all aspects of a landscape, its biodiversity, or functionality.

It’s not just about grizzly bears

Grizzly bears are important, but they are not the only species we need to consider. Conservation planning tools and strategies have evolved and can include multiple species, and even non-species aspects of landscapes, such as rare caves or climate refuges, to make strong decisions.

One example is Y2Y’s Bees to Bears wetland restoration project in Idaho. This work aims to help various sensitive species from small native bumblebees to large grizzly bears thrive. In fact, 101 hectares (250 acres) in the Boundary-Smith Creek Wildlife Management Area have been restored to help six specific species, plus many other birds and game animals, adapt to local effects of climate change while also providing a stepping stone link between important core habitats.

Another example is systematic conservation planning work by Y2Y partners in northern British Columbia. People from the University of Northern British Columbia and the Tsay Keh Dene Nation used science and Indigenous knowledge to identify priority areas for conservation across more than 4,800-square-kilometers.

The quality of grizzly bear habitat was one factor among many, including cultural and spiritual values, that helped determine the final plan. The plan is being used to help develop management for the Ingenika Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area.

What is Y2Y doing to improve grizzly bear habitat?

Keeping the Yellowstone to Yukon region wild and connected will help ensure we do not lose more grizzly populations, and therefore other species as well.

As part of these efforts, Y2Y is working to reconnect grizzly bears across the U.S. northern Rockies. Along with partners, Y2Y is protecting and restoring wildlife corridors from the U.S.-Canadian border into the central Idaho and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

This is to help grizzly bears return to their historic ranges in central Idaho, so Yellowstone bears become genetically robust over the long term. Helping grizzly bears stay connected gives hope for a brighter future for people, bears and other wildlife that share spaces.

Today, effective conservation planning must include many perspectives, forms of knowledge, data and information. Using umbrella species still has many benefits and will continue to be one tool Y2Y and partners used to make strong conservation decisions across the region — but will not be the only one.

Y2Y will keep advancing landscape connectivity, not just for grizzly bears, but the other creatures that depend on the same habitat.

You can get involved

Sources, citations and further reading:

Are umbrella species effective for connectivity conservation? Published in Conservation Corridor, December 2018.

Conservation conundrum: Is focusing on a single species a good strategy? Published in Yale Environment 360, May 2018

Technical Reference On Using Surrogate Species for Landscape Conservation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2015.

Breckheimer I, Haddad NM, Morris WF, Trainor AM, Fields WR, Jobe RT, Hudgens BR, Moody A, Walters JR. 2014. Defining and evaluating the umbrella species concept for conserving and restoring landscape connectivity. Conservation Biology 28(6):1584-93.

Barua, M. 2011. Mobilizing metaphors: the popular use of keystone, flagship and umbrella species concepts. Biodivers Conserv 20, 1427.

Caro, T. M., & Girling, S. 2010. Conservation by proxy: indicator, umbrella, keystone, flagship, and other surrogate species. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Carroll, C., R.F. Noss, and P.C. Paquet. 2001. Carnivores as focal species for conservation planning in the Rocky Mountain region. Ecological Applications 11:961-980.

Cicon, E. 2019 Surrogacy and umbrella relationships of grizzly bears and songbirds is scale dependent. (Master’s thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada).

COSEWIC. 2012. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the bull trout Salvelinus confluentus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. iv + 103 pp.

Cushman, Samuel A.; Landguth, Erin L. 2012. Multi-taxa population connectivity in the northern Rocky Mountains. Ecological Modelling. 231: 101-112.

Fish carcass tossing helps track food chain nutrients. 2012. Washington State University.

Hannon, Susan J, McCallum, C. 2004. Using the Focal Species Approach for Conserving Biodiversity in Landscapes Managed for Forestry Sustainable Forest Management Network

Heywood V.H. (ed) 1995. Global biodiversity assessment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Noss, R.F., H.B. Quigley, M.G. Hornocker, T. Merril, and P.C. Paquet. 1996. Conservation biology and carnivore conservation in the Rocky Mountains. Conservation Biology 10: 949-963

Noss, R.F. 1999. Assessing and monitoring forest biodiversity: a suggested framework and indicators. Forest Ecology and Management 115: 135-146.

Steenweg, R.W. 2016. Large-scale camera trapping and large-carnivore monitoring, occupancy-abundance relationships, and food-webs. Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 10903.

Steenweg, Robin, M. Hebblewhite, C. Burton, J. Whittington, N, Heim, J. T. Fisher, A, Ladle, W, Lowe, T. Muhly, J. Paczkowski, M. Musiani. 2023. Testing umbrella species and food-web properties of large carnivores in the Rocky Mountains. Biological Conservation, 278.

Surrogate Species: Piecing Together the Whole Picture. Written by Andrea R. Litt and Andrew M. Ray, published by National Park Service

Wilcox, Bruce A. 1984. In situ conservation of genetic resources: Determinants of minimum area requirements. National Parks, Conservation and Development, Proceedings of the World Congress on National Parks. J.A. McNeely and K.R. Miller, Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 18–30.

Thank you to Dr. Sarah Elmeligi and Kimberly Taugher for their writing and research on this post, with editing by Kelly Zenkewich and Dr. Aerin Jacob