One of Y2Y’s 2018 Sarah Baker recipients, PhD candidate Kirsten Reid developing important “baseline” for biodiversity research in the Yukon and N.W.T.

Science can provide us with information needed to help make important decisions, but the road to acquiring knowledge is anything but predictable.

This is certainly true in our world today as we navigate a rapidly changing climate, an upheaval of societal routine, and rising demand on natural systems. Research and fieldwork often also have unexpected elements — something Kirsten Reid knows well as she approaches her final year of PhD work at Memorial University.

Kirsten was one of Y2Y’s 2018 grantees for the Sarah Baker Memorial Award, which helped fund her team’s 2019 fieldwork in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories (N.W.T.) — the northern pole of the Yellowstone to Yukon region. Kirsten has been working in the north since 2015, taking a close look at how biodiversity changes as you go north and the different ways that species interact in the Canadian sub-Arctic.

Biodiversity research in northern Canada

While we can identify characteristics of the current landscape and how animals interact with it today, climate change is causing the north to warm at alarming rates — northern Canada is warming at three times the global average. As well, the Yukon and N.W.T. are increasingly vulnerable to human disturbances and rapid development.

That’s where Kirsten’s research comes in: what do these vital northern ecosystems look like now, and how do we expect them to change in face of these disruptions?

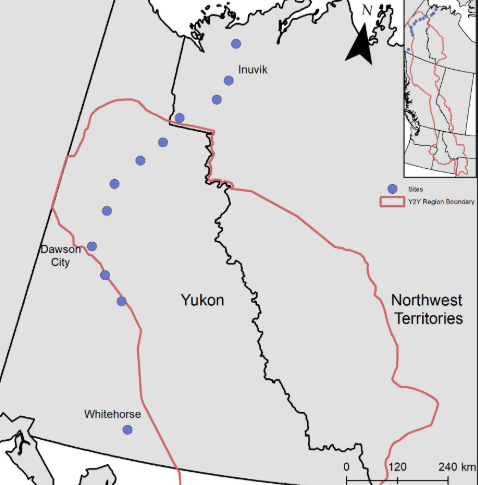

In summer 2018, Kirsten and her team set up 12 study sites across 900 kilometers stretching from the southern arctic to the high southern arctic, and set out to learn more about the region’s biodiversity. She wanted to know about the diversity of plant and animal communities and interactions among food webs — from large mammals such as caribou down to vegetation such as lichen.

“What’s unique about this region is how quickly the landscape changes — from grasslands to productive forests, then tundra, and so on,” says Kirsten. “That’s why it was so important to first understand the ecosystems at a fine scale, so I could then understand how that translates into broader scales, and how that might change in the future.”

As the northern Yukon and N.W.T. warm and precipitation patterns change, some places will become unsuitable for certain plant and animal communities that we see today. Many species will need to shift their ranges, generally upslope or northward.

Ecological connectivity helps keep natural communities healthy. For instance, it helps maintain pollination and stream flow, and allows species to migrate or move to feed, mate, and respond to climate and other environmental changes.

“Conservation in the north needs especially big picture and long-term thinking. That’s one of the things that I love about Kirsten’s research: she’s literally working from the soil up through trophic levels, helping fill in knowledge gaps about this special place.”

Dr. Aerin Jacob, Y2Y conservation scientist

As well as informing decisions about land use and management today, Kirsten hopes that her research will provide a credible baseline for the future.

Decades from now, people can look back at these data and compare what changes occurred on the landscape, why those changes happened, and how plants and animals were affected.

Summer 2019 in the field

Kirsten returned to her study sites in summer 2019 to see what happened over the past year. Remember the surprises that often come with fieldwork? While Kirsten’s research is bringing more predictability to biodiversity research in Canada’s north, she couldn’t have planned for some of these experiences!

Takeaway #1: Some animals aren’t keen on humans setting up measurement tools.

Kirsten had set up an array of measurement instruments to collect data on plants and animals in the area, including remote cameras. From bears chewing on cables, to foxes knocking down instruments and carrying a camera a whole kilometer away from its original site, one of Kirsten’s remote cameras took quite a beating. Two days after installing a replacement camera, a bear came along and hit it. Instead of facing the study site, the camera faced the highway and cost her a whole winter of data collection.

Takeaway #2: You never know who you’ll meet on the road.

Most of Kirsten’s sites are located along the Dempster Highway, a 740-kilometer gravel road that stretches from Dawson City, Yukon to Inuvik, N.W.T. While camping along the Dempster, Kirsten and her team met a group of German travelers who dedicated a polka song to them, despite not speaking one another’s languages. On another occasion, the group experienced a double-flat tire (with only one spare). Luckily, local highway workers were nearby to help.

Takeaway #3: You can never have enough peanut butter.

Peanut butter is a surprisingly helpful tool used to measure small mammal diversity. Trail cameras baited with a minimal amount of peanut butter attract northern red-backed and tundra voles, meadow jumping and the North American deermouse — all important seed herbivores in this region.

Despite some mishaps and surprises, Kirsten brims with silver-linings and enthusiasm about her work.

“When I returned for 2019 fieldwork, the area felt much more familiar, but it was also interesting to see the different patterns and anomalies on the land. Going back deepened my understanding about how the interactions between plants and animals can change, even in a relatively small study area, over just one year,” says Kirsten.

Understanding these changes, she explained, included anything from digging deeper into how wildlife might shift their ranges to asking why or why not a species of plant exists in a location and how that might affect an animal’s browsing pattern.

Y2Y’s conservation scientist, Dr. Aerin Jacob, joined Kirsten and her team in August 2019, which according to Kirsten, brought new perspective to her wide-ranging research.

“When you’re lying on the ground looking at soil moisture for days on-end, it’s easy to get stuck in your own head,” says Kirsten. “Having Aerin with us for the week gave me the chance to explain my project in a way that considers the larger landscape and the data’s applicability in other parts of the Yellowstone to Yukon region.”

The Greater Mackenzie Mountains is a huge, wild landscape. It’s also fragile and doesn’t get as much research attention as other parts of the Yellowstone to Yukon region.

“Conservation in the north needs especially big picture and long-term thinking,” says Aerin. “That’s one of the things that I love about Kirsten’s research: she’s literally working from the soil up through trophic levels, helping fill in knowledge gaps about this special place.”

A Starfish Canada ‘Top 25 Under 25’ Environmentalist

Kirsten’s ambitious work can serve as inspiration for other scientists and youth who are eager to make a difference. That’s why we weren’t surprised when earlier this year, Kirsten was recognized as one of Starfish Canada’s Top 25 Environmentalists Under 25.

“It was incredibly cool to be on such a diverse list of recipients, and I think it shows that age doesn’t determine whether or not you can make a difference,” says Kirsten. “Not only is it great for youth to see what other youth are doing, but also for everyone else. Maybe it will help encourage other young people to say ‘Hey, if they can do it then so can I’.”

Learn more about the preliminary results of Kirsten’s research, which she recently presented at the online 2020 conference for the International Association of Landscape Ecology. You can also learn more about Kirsten’s project in this March 2019 article.

The Sarah Baker Memorial Fund supports early-career researchers whose projects advance Y2Y’s conservation strategy and result in tangible benefits within the region. Sarah Jocelyn Baker’s appreciation for the natural world and ability to find solutions resonate with the aspirations and vision of Y2Y. We are honored to carry her spirit forward through the Sarah Baker Memorial Fund. Thanks to a gift from her extended family, Y2Y can offer grants to post-secondary students and postdoctoral fellows pursuing environmentally related studies in any post-secondary institution in Canada or the U.S.