Keeping people safe and wildlife connected across the Rockies

In British Columbia, there are roughly 10,000 wildlife-vehicle collisions each year, which cost upwards of $25 million.

The economic and physical cost of these accidents on humans is well-known, but the effect on wildlife populations is more complex and goes beyond just roadkill.

The good news? There are proven solutions to this growing problem. Various partners, including Y2Y, B.C.’s Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, Wildsight, Liber Ero Fellowship Program and Miistakis Institute are working together in one part of the province to make a difference.

Highway 3: A “collision course” for wildlife populations

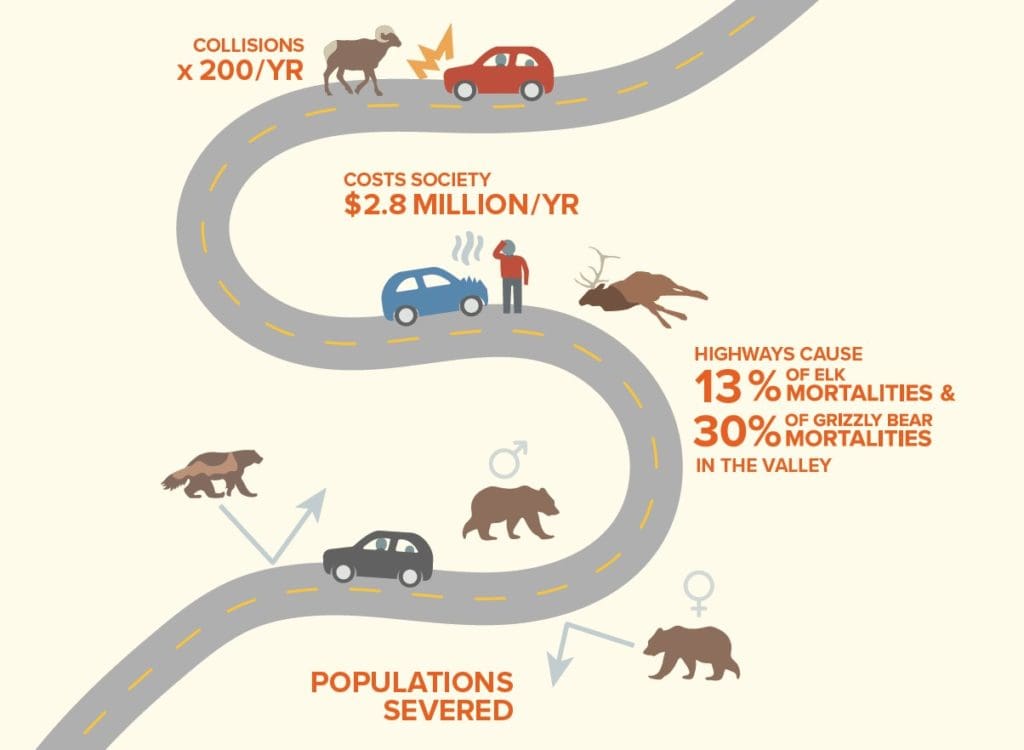

British Columbia’s Elk Valley is home to iconic, wide-ranging animals such as grizzly bear and wolverine, elk and bighorn sheep. For many of the area’s large mammals, this highway is a mortality source and blocks movement at a local (Elk Valley) and continental (Canada/USA) scale.

Approximately 200 collisions with large mammals occur each year on Highway 3 between Hosmer, B.C. and the Alberta border. This costs society $2.8 million annually.

If this continues, wildlife populations will continue to be at-risk of severe declines and connections between populations could be permanently severed.

The problem: High rates of wildlife-vehicle collisions

The solution: Crossings and fencing for better connectivity

Reconnecting the Rockies

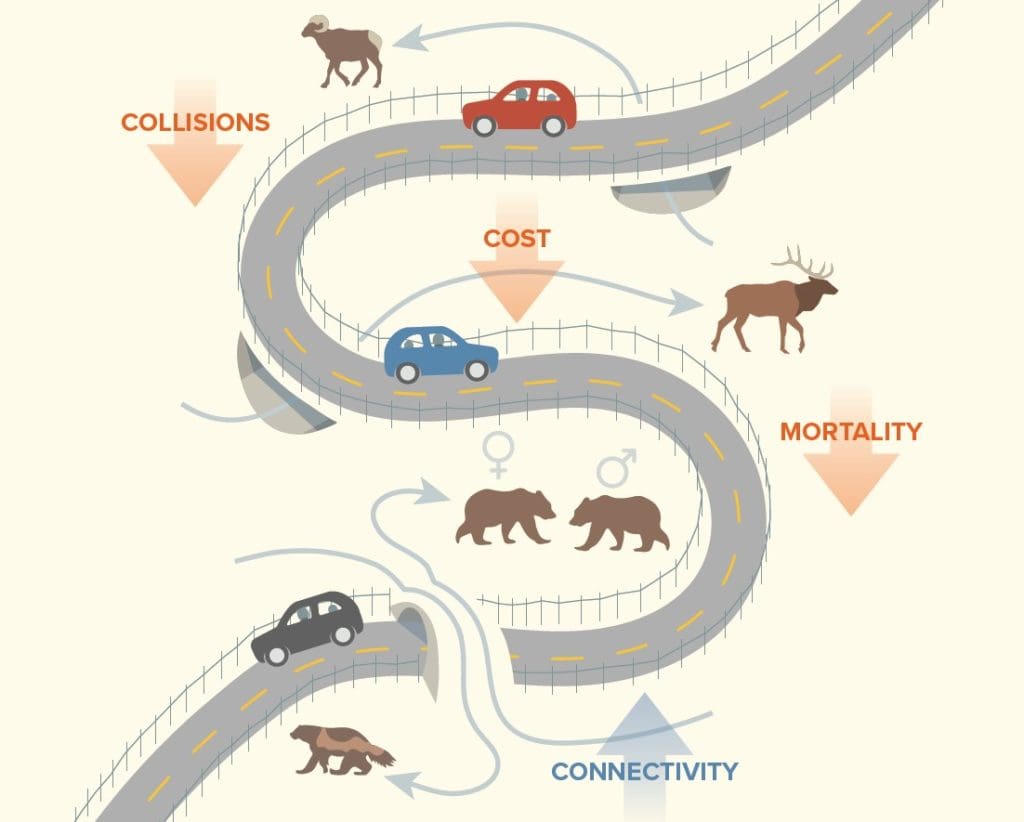

By developing a system that keeps wildlife off the road and allows them to move safely via a series of underpasses and overpasses connected with fencing, the Reconnecting the Rockies project team is working to fix this problem.

In 2019, a diverse group of stakeholders including provincial and local government, industry, conservation organizations, and scientists gathered to update highway mitigation plans. These plans were evaluated using updated wildlife tracking data, road kills, and local knowledge.

Mitigation projects elsewhere have reduced collisions by 80 to 90 percent and with these roadkill reductions, the B.C. government expects the mitigation work to pay for itself in 10-20 years.

Phase one consists of retrofitting existing bridges to act as wildlife underpasses. The areas underneath bridges will be landscaped to increase movement potential for species such as grizzly bear, elk and deer. We will then fence the highway in between these structures to keep wildlife off the road and guide them to crossings.

While this works takes place, partners are working to secure funding for phase two: B.C.’s first major wildlife overpass outside a national park.

S. G. Hesse, Collisions with wildlife: an overview of major wildlife vehicle collision data collection systems in British Columbia and recommendations for the future (2006).

T. Lee, T. Clevenger, C. T. Lamb, Amendment: Highway 3 transportation mitigation for wildlife and connectivity in Elk Valley of British Columbia (Fernie, B.C. 2019).

M. F. Proctor, B. N. Mclellan, C. Strobeck, Population fragmentation of grizzly bears in southeastern British Columbia, Canada. Ursus. 13, 153–160 (2002).

A. Clevenger et al., Highway 3: Transportation mitigation for wildlife and connectivity (Fernie, BC, 2008)

Center for Large Landscape Conservation, Reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions by building crossings: general information, cost effectiveness, and Case Studies from the U.S. (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2020).