For Ph.D. student and 2024 Sarah Baker grant recipient, Eli Estey, his interest in studying wolverines is rooted in finding balance between wildlife conservation and the people who share their landscapes with the species.

Through his interdisciplinary research at the University of Idaho, Eli is tackling an essential question: How can we manage wolverines under their new Endangered Species Act protections in the United States while also respecting the needs and perspectives of local communities?

A scientist rooted in community

Growing up in small rural towns, Eli always knew he wanted to stay connected to nature in his work.

His passion for the natural world led him to wildlife biology, but it was his deep connection to rural communities that shaped his approach to research.

“I’ve never been someone who likes to go an inch wide and a mile deep. I’ve always taken a broader, more interdisciplinary approach,” Eli explains.

His work blends wildlife biology, education, and community engagement — three elements he believes are necessary for successful conservation.

Understanding perceptions of wolverines

Wolverines are said to be one of the least understood carnivores in North America.

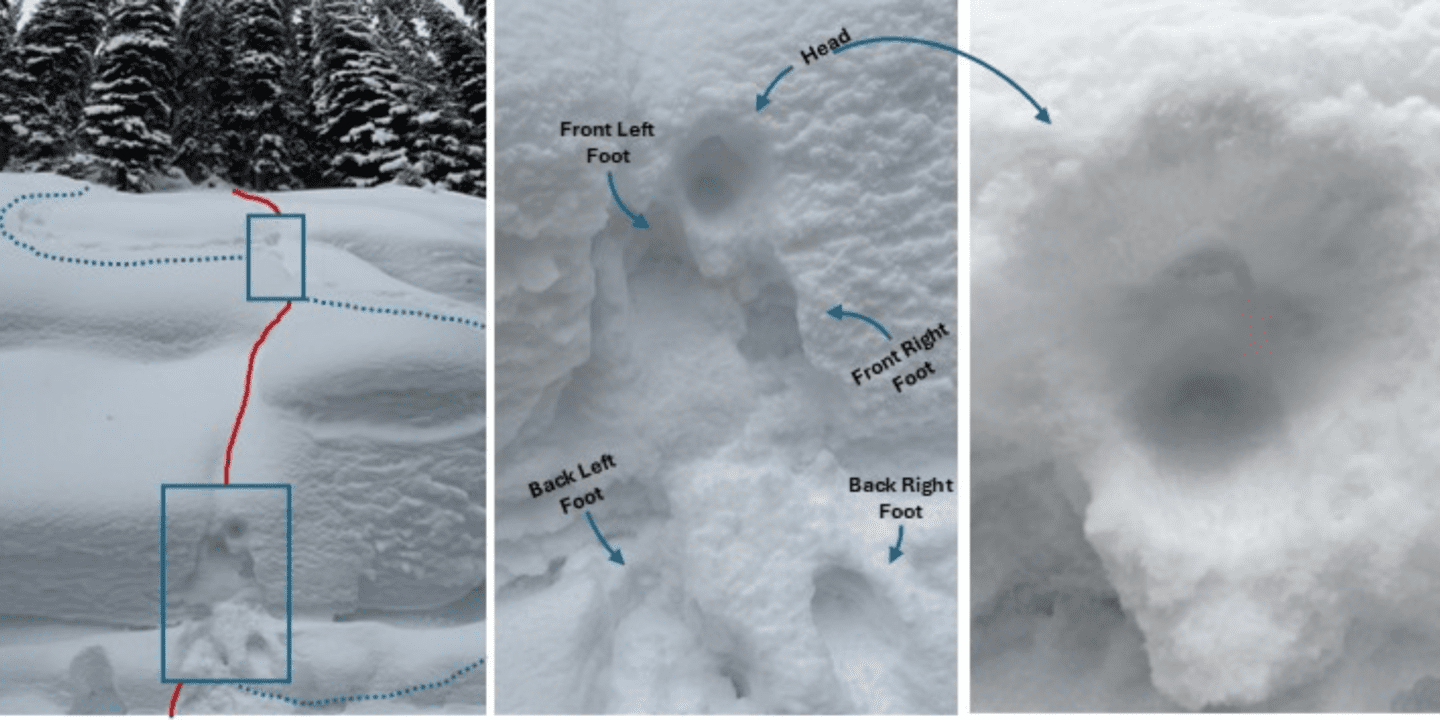

The wolverine (Gulo gulo) is a compact but capable member of the weasel family that defies its modest 13-kg (30-pound) size. Despite having no relation to wolves, as their name might lead you to believe, these hardy creatures are perfectly adapted for life in harsh winter conditions, with thick, oily, frost-resistant fur and large, snowshoe-like paws.

“The first peer-reviewed Western scientific study that substantially outlines wolverine ecology only came out in the 1980s,” Eli points out. “That’s incredibly recent when you compare it to species like white-tailed deer, which we’ve been studying for well over a century.”

This gap in knowledge has ultimately contributed to misconceptions — many people view wolverines as aggressive and dangerous, though they rarely interact with humans.

Wolverines are incredibly strong and tenacious, capable of challenging grizzly bears for their kills. They also possess remarkable endurance, traveling up to 800 kilometers (500 miles) in just days and scaling near-vertical mountain faces in winter conditions.

However, these solitary animals are also surprisingly vulnerable. They require vast territories, with researchers estimating just one wolverine per 500 km2 (190 square miles), and females depend on persistent spring snowpack for denning. Their highly territorial nature means they won’t share their range with others of the same sex, making them particularly sensitive to habitat fragmentation.

“Information has only started coming in the last 40 years, as far as Western science goes. Of course, Indigenous communities in North America have been observing wolverines since time immemorial. But Western science is a different story. And in my eyes, that’s led to this kind of disconnect.”

“Information has only started coming in the last 40 years, as far as Western science goes. Of course, Indigenous communities in North America have been observing wolverines since time immemorial. But Western science is a different story. And in my eyes, that’s led to this kind of disconnect”

With the species recently listed as threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act as of November 2023, new management strategies are needed, and understanding public perception is critical to their success.

Surveying winter recreationists

Eli’s research focuses on a key group: winter recreationists. Why? Because wolverines depend on deep, persistent snowpacks for denning, and those same areas are popular for people backcountry skiing, snowshoeing, and snowmobiling.

Through both in-person intercept surveys with recreationists at trailheads and QR code posters in Idaho’s Payette National Forest, Eli’s team is gathering data on:

- Awareness: Do recreationists know that wolverines live in these areas?

- Beliefs: What are their values held toward the wolverine?

- Management acceptance: To what degree do they support seasonal use restrictions around wolverine dens?

Understanding these perspectives will help land managers make informed decisions that work for both wildlife and people.

“We’re not just asking how to best protect wolverines, but how to do so in a way that considers the wants and needs of the communities that rely on these landscapes,” says Eli.

Embracing community perspectives

A key element of Eli’s research is fostering open conversations with winter recreationists. Rather than seeing differing opinions as obstacles, he embraces them as opportunities to understand concerns, share knowledge, and find common ground.

“I’m not wary of pushback — actually, it’s exactly what I’m looking for,” Eli says. By engaging with both motorized and non-motorized recreators, his goal is to identify shared priorities and explore solutions that work for both people and wildlife.

His approach is rooted in respect and collaboration, ensuring that decisions about wolverine management include input from those who live and recreate in these landscapes.

“People want to be heard. This research isn’t about restricting access — it’s about working together to protect an incredible species while ensuring outdoor recreation remains a valued part of the community,” he says.

“There’s definitely a segment of the community that’s skeptical. They worry that participating in research will result in restrictions on their activities. But the goal here is to gather perspectives so that decisions can be made while considering public input.”

Engaging the next generation of nature lovers

Eli is also leading a place-based K-12 education initiative at the University of Idaho’s McCall Outdoor Science School (MOSS). Through this program, Eli hopes to foster a sense of connection to species like the wolverine through experiential learning.

Through creative activities, such as making wolverine “trading cards” before and after learning sessions, students are asked to reflect on how their understanding of the species changes over time. The curriculum is being continuously refined through participatory action research, ensuring it meets both educational and conservation goals.

“I believe education plays a huge role in shaping how people engage with conservation later in life,” Eli notes. “Maybe some of these kids will grow up to be advocates for species like the wolverine.”

Fun facts about wolverines

- Snowshoe superpowers: Wolverines’ massive feet act like built-in snowshoes, allowing them to move easily through deep snow. “Their paws are about the size of a human hand,” Eli says. “If you shook a wolverine’s hand, it’d have a solid grip!”

- The rarest of sightings: Despite spending years tracking wolverines, Eli has never actually seen one in the wild — a testament to how elusive these animals are. “It took 10 years of full-time fieldwork for anyone on my old research team to finally see one in person!”

- Valentine’s Day babies: Wolverines tend to give birth around February 14 — a perfect symbol of the species’ resilience in deep winter conditions.

What’s next?

Eli is now in the data collection phase, and his findings will soon provide crucial insights for wildlife managers in Idaho and beyond. His research will help ensure that conservation strategies will ensure protections for wolverines while also considering the perspectives of those who share their habitat. What’s more, this research will help us better understand the needs of wolverines across the Yellowstone to Yukon region.

At the heart of his work is a belief in balance — between people and wildlife, between science and education, and between conservation and recreation.

“At the end of the day, we all just want to be able to enjoy these incredible landscapes, whether we’re humans on skis or wolverines in the snow,” says Eli.

The Sarah Baker Memorial Fund supports early-career researchers whose projects advance Y2Y’s conservation strategy and result in tangible benefits within the region. Sarah Jocelyn Baker’s appreciation for the natural world and ability to find solutions resonate with the aspirations and vision of Y2Y. We are honored to carry her spirit forward through the Sarah Baker Memorial Fund. Thanks to a gift from her extended family, Y2Y can offer grants to graduate students and postdoctoral fellows pursuing environmentally related studies at post-secondary institutions.