The word Wanuskewin entered my world during an introductory anthropology class at the University of Saskatchewan. My professor described an ancient site that signified historical and cultural importance for the Plains Indian peoples living in Saskatchewan. She urged the class to go visit the site and explore archaeological materials that had been excavated there to learn more about Indigenous spirituality, history, and culture.

Although bison had not roamed the grasslands in nearly 150 years, the museum housed a vast array of artifacts illustrating bison as the primary resource for food, clothing, shelter, and tools. From the archaeological evidence displayed at the museum, it was clear that the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and bison was an important one.

Years later, on the tail-end of my Masters in Anthropology, I opened my phone to hear about Wanuskewin again. A headline read: Bison to Return to Saskatchewan Grasslands.

Investigating further, I visited the Wanuskewin Instagram page where a post detailed a partnership with Parks Canada and the goal of reintroducing Plains bison to their natural home in the Prairies around Wanuskewin near modern-day Saskatoon. This follows work in Alberta where wildlife rehabilitation is an important part of conservation and maintaining ecological integrity for Canadian landscapes.

Intrigued, I followed the story with genuine interest and, through a friend who worked at the park, was invited to tour the newly renovated facility.

Driving up to the park, I realized that I hadn’t been there in some time. It had certainly changed over the years. A large tipi-like structure rose out of the roof of the interpretive centre. Floor to ceiling glass windows outlined the building and statues of plants and animals dotted the grounds. I was impressed to see a large amphitheatre, playground, café, and several exhibits.

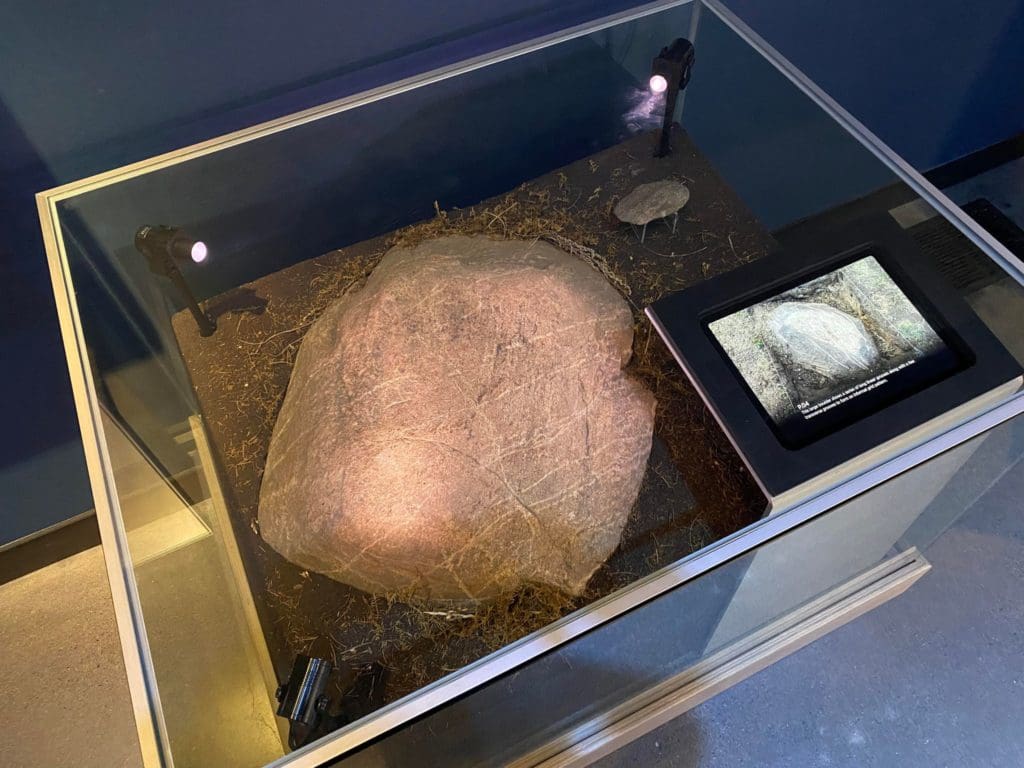

Making my way through the galleries, I was drawn to a particularly compelling artifact on display; a ribstone. A nearby bison jump called Newo Asiniak, Cree for Four Stones, is home to a great deal of evidence illustrating what life was like for the Plains Indigenous groups who live in Southern Saskatchewan.

The bison ribstone dates to somewhere between 300 and 1,800 years old. On it, petroglyphs meticulously carved into the rock depict a bison ribcage. At the centre, there’s a spiritual human-like figure in the shape of a bison, with horns and a tail. The stone is a meaningful find because it connects Indigenous groups to bison through historical, cultural, and spiritual intersections.

Wanuskewin is a unique place. In Nēhiyawēwin, or Plains Cree, it means “sanctuary.” Apt, as it was an important gathering place for the people of the Northern Plains.

Today, this place advocates for the merging of scientific and cultural knowledge, including spiritual knowledge. Here, the connection between Indigenous groups and bison is bound by necessity as subsistence hunting, but also by spirit — making the link familial.

In this way, bison are not only resources, but ancestors who teach Plains Indian Indigenous community-members different ways of knowing. Inter-species kinship is a cross-cultural understanding of family, and I was taken with this notion that humans and animals are not just dependent, but related.

In my own considerations of conservation and what that can look like, not only throughout Saskatchewan, but in my life as well, it is absolutely thrilling to observe creative reconciliation initiatives; particularly those that are embedded in fostering lived experience.

When I think of a cultural museum, I think of exhibits that house artifacts behind class cases. There is nothing wrong with this, and there are certainly more traditional exhibits at Wanuskewin — however, being able to see and experience living spirits on sacred lands is just something you cannot glean from an exhibit caption.

It was the energy of the landscape that resonated with me. Walking along the paths that wind their way through the valley is a special experience. You are surrounded by natural life. Trees, bushes, berries, bugs, birds, deer, and the odd coyote are just some of the many different species you will encounter.

The expansive river running along the site creates a beautiful melody of sound as you sit among the grasses, feeling the sun on your face, and reflecting on how the energies around you move with the energies in your body.

Seeing the bison for the first time was a powerful experience. I walked up to the pen and was met with a strange buzzing on my skin. After a moment, I realized vibrations from a low but audible hum were travelling through the air to rest on my body. The herd was sending out a unified warning call.

Looking, I could understand why. In the centre of their protection circle stood a baby bison. The little face curiously peeked through the mass, looking out to catch a glimpse of me. I felt compelled to lower my body to the ground; immediately humbled by the overwhelming sensation of being before such majesty.

I sat there for a moment and simply enjoyed the space between us; the herd and myself. I looked into the eyes of the mother bison who stood, unmovable, like a brick wall between her baby and the rest of the world. Her deep brown-black eyes seemed to say, “We are here now. You are welcome to visit, but don’t get too close. This is our home now.”

The Plains bison history is deeply rooted in the Wanuskewin site. In 2019, heifer calves were brought from Grasslands National Park in southwestern Saskatchewan. Bull calves were brought from the United States. Interestingly, each of the bison brought back to Wanuskewin share genetic pedigrees that are descended from remnant bison herds from the late 1800s. They are descendants of the herds that once roamed the Northern Plains.

I am moved by this — it is a concentrated and actionable step towards reconciling the land. Using bison that share genetic history to the original inhabitants of the land is also deeply respectful of the site. It acknowledges the past while looking toward a thoughtful and inclusive conservation future.

Bison are back

Across the Yellowstone to Yukon region, communities are working to bring bison back to the landscape. Bison recovery has important implications for the landscape as a keystone species. North America’s largest land mammal are often referred to as “ecosystem engineers.” This is because their presence shapes all sorts of interactions in habitat related to their grazing, wallowing, deaths and other natural behaviors. Their reintroduction and recovery also have important cultural implications for Indigenous peoples.

Banff National Park

In 2017, 31 bison were reintroduced to Banff National Park’s Panther Valley after being absent from the park for 160 years. Indigenous communities were involved in the process, including consultation and a blessing ceremony on the shore of Lake Minnewanka with Buffalo Treaty signatories to welcome the herd, and a second ceremony at Elk Island National Park to mark the departure of the herd to Banff. Scientists with Parks Canada are now studying the effects this reintroduction is having on the landscape. As of 2022, the herd is thriving, with around 90 animals.

Blackfeet Confederacy

Launched in 2009, this effort includes bison as part of maintaining and restoring nature and people along the Rocky Mountain Front. One aspect is on new protected areas to provide a home for bison to return to as a driver of culture and nature on Blackfeet territory. The Iinnii Initiative is run by four tribes that make up the Blackfoot Confederacy: Blackfeet Nation, Kainai Nation, Piikani Nation, and Siksika Nation.

Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone is the only place in the lower 48 states to have a continuously free-ranging bison population since prehistoric times. As a result, the population here has been an important part of the conservation of wild bison elsewhere in North America. This is not without its challenges, however. Increasingly, bison roam beyond the park borders onto private land and land managed by other agencies, where they are considered livestock and require careful management.

Waterton National Park

In 2021, six plains bison were welcomed to Waterton Lakes National Park in southern Alberta by Blackfoot Confederacy elders from Kainai Nation, Piikani Nation and Siksika Nation. The area hosts a number of buffalo jumps, many sites only uncovered after the 2017 Kenow wildfire. The bison returning was thanks to collaborative work of Blood Tribe and Parks Canada.

This article was written by Marley Duckett, one of Y2Y’s 2022 story gatherers. These four unique people are sharing personal stories, memories and places related to the special landscapes of Alberta’s Eastern Slopes, often perspectives that are underrepresented in mainstream media. Read other stories in this series.

We are grateful for the financial support provided by Alberta Ecotrust and The Calgary Foundation for our story gatherer series.