The hamlet of Grande Cache is on Highway 40 approximately 208 kilometers (130 miles) northwest of Jasper and nestled in the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains.

Some people compare the two small communities because of the similarities of their mountainous surroundings, however they are very different.

Jasper boasts the National Park that allows a variety of species to thrive within its safe confines, just outside the park borders Grande Cache is surrounded by dense boreal forested areas and rich habitat.

This is one of the reasons this area of Alberta’s Eastern Slopes is a stopover point for many birds that migrate long distances from further south. This route is one of several flyways in Canada, and home to many places birds use as they go back and forth each year as far north as the Arctic Circle to their wintering grounds in the south.

It is here within the wilds that many species of migratory birds can be seen. This is a perfect place to watch, learn and record some of the many different avian visitors.

One such avid fan is photographer Tom McDonald. Owner of Eagle Child Images, Tom is an Aseniwuche Winewak Nation member and photographer who has lived in the Grande Cache area for all of his life.

He has spent many hours capturing some incredible wildlife photos, including large species such as grizzly bears, caribou and moose. Over the years, Tom has honed his skills and through his art and says he conveys his interconnectedness with the land via his lens. While he still loves to photograph large animals, bird photography has become a new passion.

Armed with his Nikon D-500 camera and a variety of lenses, Tom loves to photograph these temporary residents as they fly through. He explains that over the years he has acquired experience and learned how important it is to know the gear that you are using and about the moving parts. Incredibly, he does not use a tripod but uses a handheld method.

“Bird photography is challenging, they just don’t sit and wait,” Tom says.

Unlike family portraits, there is no posing and that is why he enjoys it. Tom adds that his photos are, “A reminder that he is part of this beautiful creation. I am blessed to be able to do what I do spending time on the land”.

Using both his photographic skills and location in the Central migratory bird flyway, Tom has amassed a large archive of unique feathered friends. The following images are of birds that are protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act of 1994.

Find the Cree names for these birds at the Cree Literacy Network: piyêsîsak – birds.

Tiny traveler: Calliope hummingbird

Calliope hummingbirds (Selasphorus calliope) are the smallest long-distance flying migrants in the world.

Tiny, weighing about the same as a ping pong ball, this hummingbird is the smallest North American bird. Its size makes it an extraordinary feat as it migrates up to 8,000 kilometers (5,000 miles) to and from warmer wintering grounds in Mexico as far north as Smithers, B.C., via an inland route along the Rocky Mountains.

Tom first saw a calliope in a magazine and was stunned. Within the year he saw one at his parent’s house at Grande Cache Lake, eventually capturing this photograph in June 2012.

Wildlife is unpredictable, so he never takes anything for granted. Part of his knowledge comes from so much time spent in a natural environment where he has learned to observe behavior.

For example, in the case of this calliope, he waited to see if there was a pattern to its movements. Every 20 minutes or so the bird would return for the food his parents had left out. As a result, Tom captured hundreds of pictures. Each shot is slightly different than the next but just as fascinating.

“These shots only happen with patience,” says Tom.

Fast flyers: Rufous hummingbird

Another small migrant is the rufous hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus). During migration they pass through mountain meadows as high as 12,600 feet to feed nectar-rich, tubular flowers. Like the calliopes these aggressive, feisty birds also often winter in Mexico.

Rufous hummingbirds are wide-ranging and breed farther north than any other hummingbird species. Each year they make a circuit through western North America, spending spring in California and Mexico, summer in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, and fall in the Rocky Mountains. This behavior makes it vulnerable to the effects of climate change since it relies on finding the right conditions in so many different habitats at just the right times.

Tom took this photograph in his own backyard in June of 2015. That summer he focused purposefully on hummingbirds, and he was lucky to see many rufous hummingbirds in and around Grande Cache.

The rare charmer: Chestnut-backed chickadee

In this stunning snapshot, the chestnut-backed chickadee’s (Poecile rufescens) colors match the rich brown bark of the trees it lives among. This noisy little bird is social and quite active and can often be found foraging through the conifers.

One thing that stands out for this kind of chickadee is that their nests are often more than half animal fur. Although the chestnut-backed chickadee is not truly a migratory bird, it is known for its seasonal movements, flying higher in the mountains during late summer before returning to lower elevations for winter.

Tom snapped this photo of the chestnut-backed chickadee near his sister’s house near Grande Cache in December 2017. This is the only one he has ever seen. When he first saw it he thought it was a boreal chickadee.

His process for identification is to take as many photographs as he can to download and study them later at home, often using bird books to help identify a new “face.” In this case, he was not quite sure what he had photographed, so he turned to another resource, a bird group he belongs to.

After sharing his picture of the unusual chickadee, someone encouraged him to contact an expert. Tom sent photos of this mystery bird to Dr. Jocelyn Hudon, curator of ornithology at the Royal Alberta Museum, and learned that the Alberta Bird Record Committee had fewer than 15 documented records of this species in the province at that time.

This sparked extra interest in the rare bird and a select few came to watch and study this bird, three or four times a week for four months. It was very exciting to share such a find.

“I have never seen one since,” says Tom.

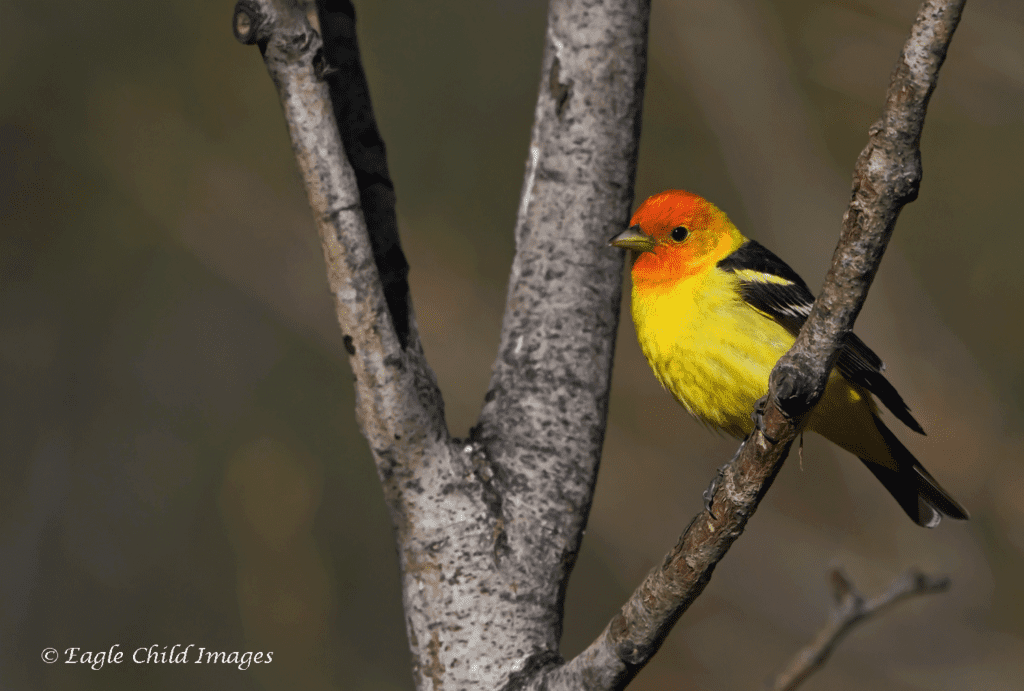

Bright bird: Western Tanager

Western tanagers (Piranga ludoviciana) spend their breeding season in open conifer forests. This species ranges farther north than any other tanager, often well into Canada’s Northwest Territories. The Western tanager may spend as little as two months in the cooler climates before migrating south again.

With orangish heads and bright yellow body, male Western tanagers are flashy, to say the least, while females and young Western tanagers are a muted yellow green shade. These birds live in open woods all over western North America, and they particularly love evergreens. In the summer you will likely hear their distinct calls in the woods.

This Western tanager Tom photographed in June of 2022 was another visitor to his sister’s yard. He shared that he has observed the Western tanager regularly since 2008.

“Usually, they have been in small groups of maybe five at a maximum,” he explains.

In some of his photos he has more than one tanager — a rare sight. One of the reasons he believes that there have been more sightings of them in this area is due to climate change.

“Animals are more in tune with these kinds of things, they can sense things we cannot,” adds Tom.

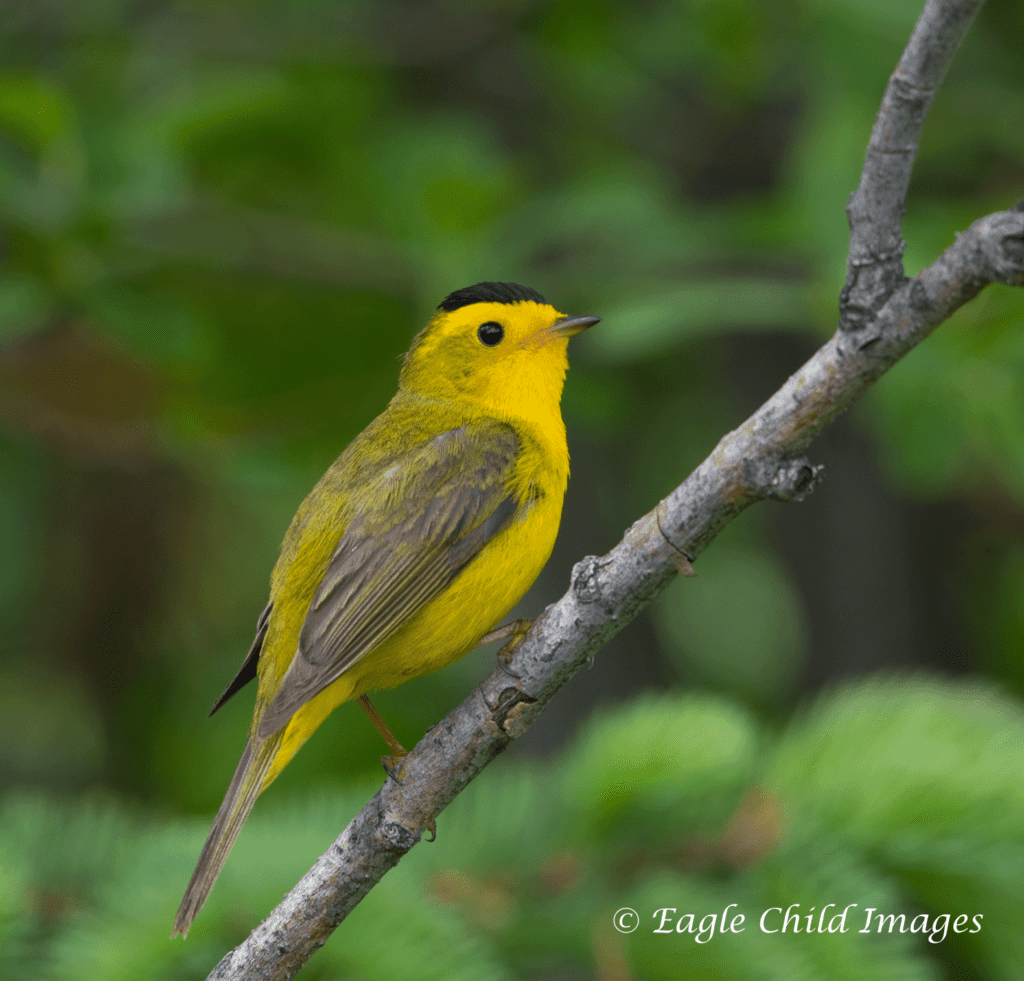

Sweet songbird: Wilson’s warbler

Wilson’s warblers (Cardellina pusilla) love mountain meadows and areas near water — you are most likely to spot them among willows and alders along streams.

Due to differences in spring and fall counts, it seems some populations use slightly different routes for their seasonal migrations. Male Wilson’s warblers tend to migrate before females, a move experts think is likely to establish breeding areas. Winters for the Western populations tend to be spent in Mexico, with populations heading as far north as Alaska in some cases.

The Wilson’s warbler Tom photographed in June 2021 was 45 minutes northeast of Grande Cache. According to Tom, Wilson’s warblers are common here, and while he has witnessed multiples of the bird, it’s not quite an abundance. Spring migration is the time when spotting them is most likely.

However, Tom says 2022 for example was different as spring was late but there could be other reasons that have impacted the birds.

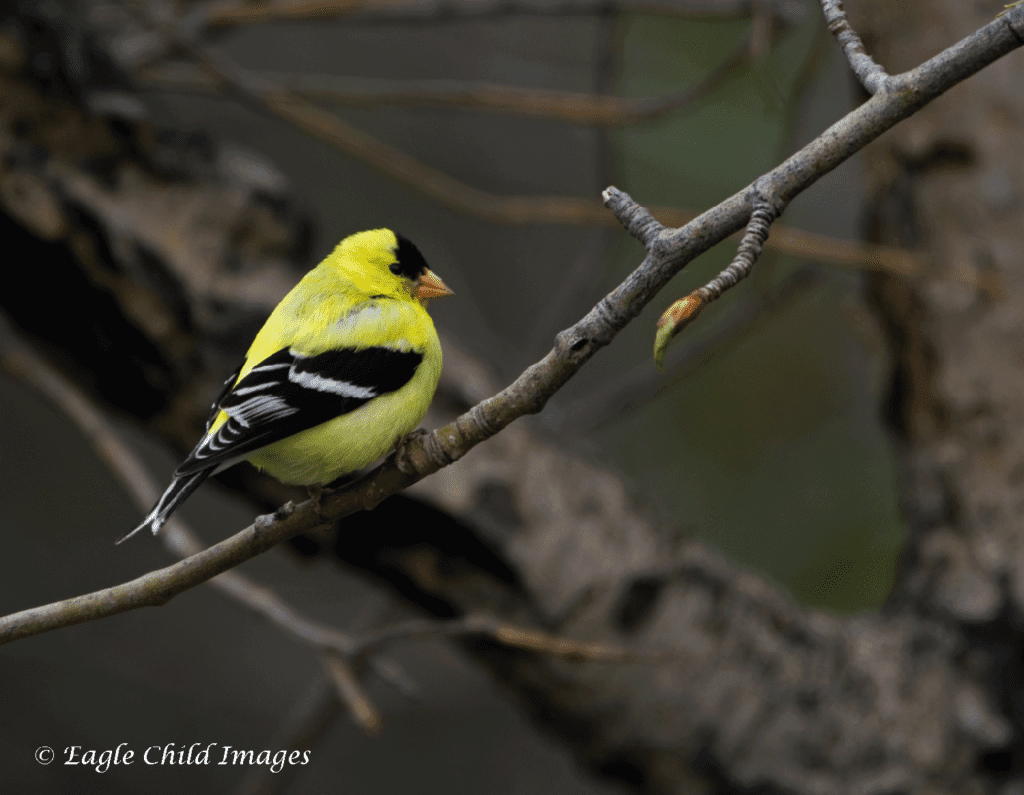

Yellow blaze: American goldfinch

A bright, almost neon, yellow, the American goldfinch (Spinus tristis) is hard to miss. These vibrant yellow birds are most often spotted in fields and floodplains — any place with lots of thistles and asters.

Relatively common, American goldfinches have some behavior that befuddles scientists. This bird is a late breeder, usually nesting from July to September. Some experts believe this behavior is tied to its reliance on seed and the fact that they molt feathers. Seed is not as protein rich as other food sources, and molting is hard on a bird, making the energy demands of breeding especially challenging, and creating a need to feed more before mating.

Tom saw this American goldfinch in May 2022 in his sister’s backyard. It only hung around for about a week, but he managed to capture some great shots.

Usually there are many American goldfinches, however 2022 Tom reposted not as many sightings. This may be related to Alberta’s outbreak of avian flu, that affected both domestic and wild birds.

Provincial officials state the outbreak was worst in April and May. During spring migration, there were several deaths among traveling birds, including snow geese, Canada geese and other waterfowl, as well as raptors. The virus was present over a broad area of southern, central, and eastern Alberta, and eventually the northwest.

Following expert advice, Tom says he took extra care with his bird feeders to avoid spreading illness among the visiting flocks.

The Eastern Slopes offer a bounty of memorable sights, especially to those in the right place at the right time. Whether it’s a rare bird visiting for a season, a flash of aurora borealis in the night, or a grizzly bear waking from winter slumber, Tom hopes to be there to capture the rare moments around him.

These images show off just a small selection of a huge collection of birds and other wildlife Tom has taken through the years. These days, Tom continues to chase the light and explore the landscape in and around his home, hoping for a glimpse of nature at work.

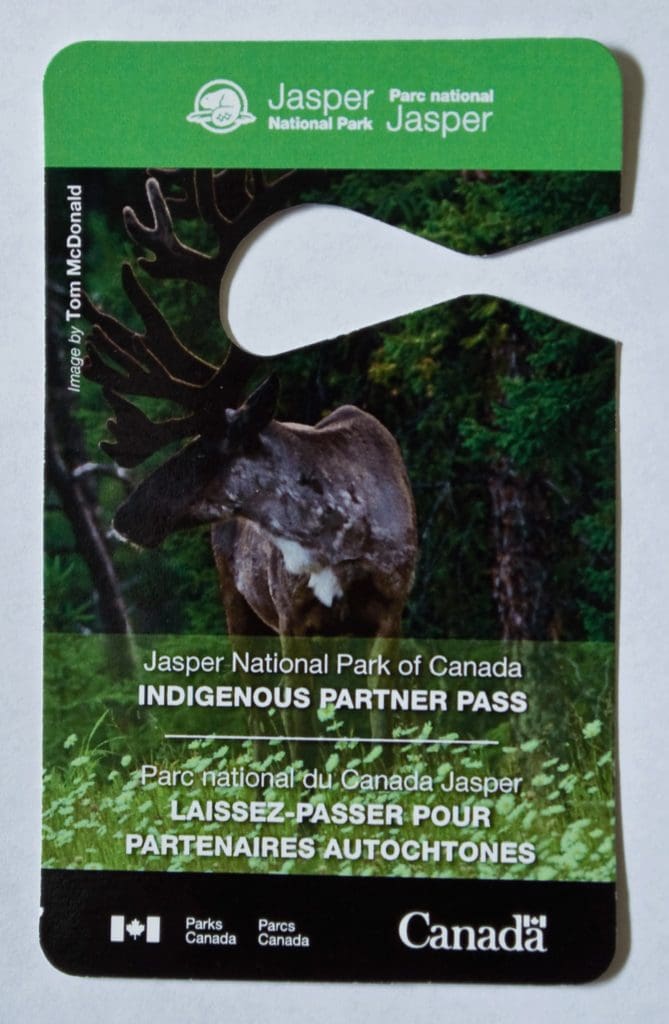

His talents are getting noticed, too. In 2021 Parks Canada requested art or photography submissions from Indigenous partners for the annual Jasper National Park Indigenous Partner Pass. Tom’s photo of a bull caribou from the nearby herd was selected.

“We are spoiled to live in this beautiful country that surrounds us. Lots of places to go and see if you take the time to appreciate it,” he says.

Follow Tom McDonald’s excellent photography of birds and other species on Facebook: Eagle Child Images.

This article was written by Renee Fehr, one of Y2Y’s 2022 story gatherers. These four unique people are sharing personal stories, memories and places related to the special landscapes of Alberta’s Eastern Slopes, often perspectives that are underrepresented in mainstream media. Read other stories in this series.

We are grateful for the financial support provided by Alberta Ecotrust and The Calgary Foundation for our story gatherer series.