Nature is for everyone. This extends to physical, economic and social access. To be truly accessible, we need to consider the sorts of barriers that are keeping people from nature.

Riding a bike down the Myra Canyon Trestles trail in Kelowna, B.C., I experienced a taste of what it is like to be excluded from outdoor spaces and recreation. The truth is, I have complicated feelings about being in nature as a bigger bodied person.

This happened one summer immediately after completing field work in rural Alberta for my graduate thesis. A long-time friend invited me to her family’s vacation home in B.C.

She had spent years describing the setting of her childhood family vacation spot and I was excited to see where she spent so much of her time. I had never been to the area but was excited for a change of scenery and to decompress from my academic studies, so I quickly accepted the invite. If it was half as beautiful as the images of hikers traversing rocky cliffsides and wooded landscapes that dominated my Instagram feed, I knew I’d have a great time.

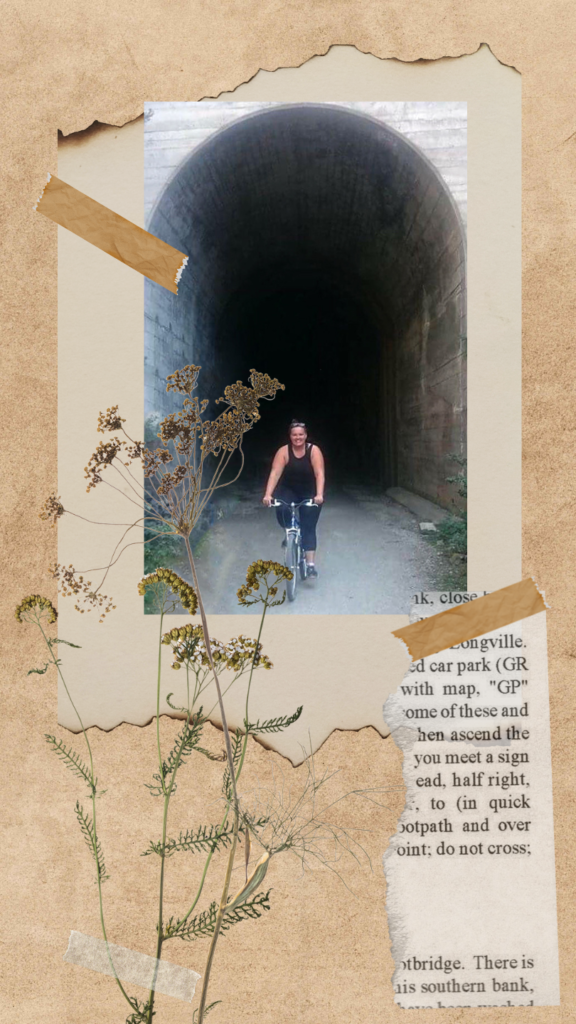

One day, my friend and her aunt invited me on a cycling trip. Now, I admit I don’t love biking. As a heavier person, it often makes my knees ache for days afterwards, but my friend’s aunt assured us it was an experience like no other.

The trestles encompass a portion of the Kettle Valley Railway and run along a canyon. The walls of the canyon are very steep, and consist of bridges, built by hand. Waterfalls, forest, and breath-taking views of the valley from 3000 feet? Count me in!

It’s so difficult to describe how a view can make you feel. Winding through massive Douglas firs and Ponderosa pines stretched out in front of us, reaching towards the sky; a cathedral of branches and clouds. I can see why people are drawn to this place; it was almost sacred.

At that altitude, I expected the wind to push us into the cliffside but instead, it swirled around us, picking us up from the base of the bike, like wind to sails, and pushed us faster and faster along, sailing past kilometer markers.

At the 3-km mark, however, things started to change. That’s when the check-ins started. My friend and her aunt would pull off at rest points to see if I was good to keep biking and to remind me, we also had a return trip to make.

This was confusing to me. I’d been feeling great, it didn’t even feel like work. The valley before us was rich in greens and blues, it seemed like the top of the world. I felt the fear of my biking ineptitude melt away, the loneliness of fieldwork evaporated in seconds, overcome by the wonderful and rare awareness of loving your life at the exact moment of living it.

Throughout my childhood, I always felt fit and strong. I had never really thought twice about my body unless other people told me about its flaws. It wasn’t until these people told me that I was fat, or tall, or too muscular for a woman, that I would look at myself in the mirror and question what those descriptors meant about who I was.

Was I not biking the same distance? Was I not out here enjoying the same view, the same rush, the same thrill of this beautiful place? Was I not biking well or something?

Near the half-way point of the tour, my friend and her aunt chimed in with “helpful” reminders.

“Don’t forget, we still need to bike back!”

“Just let us know what you need, you don’t want to push it — these trails are hard for anybody.”

Ah. You don’t want to push it — these trails are hard for anybody. There it was.

I got off my bike, feeling the heat of embarrassment and shame creep over my face. I walked over to a viewpoint and busied myself with taking photos. I needed a moment to process the overwhelming emotional sting of their judgements. Their repeated ‘check-ins’, kilometer after kilometer, were like little jabs, telling me that I wasn’t athletic or fit, and for me, it translated into ‘you don’t belong here.’

At the 9-kilometer-mark, the tension was building. My friend’s aunt asked if we were done.

“It’s up to Marley,” said my friend. Not wanting to be outdone, I flipped it back to her, claiming I could do another 9-km if she could.

Finally, my friend turned away saying, “Well, I think I have reached my limit today. I think 18 kilometers on a bike ride is pretty good. Let’s head back.”

The bike ride back was reflective. I thought a lot about the intersection between body image, womanhood, and the environment.

Outdoors spaces are often not always safe for everyone. They can be places of shame and judgement. Often these ideas are shaped by beauty industry standards, mainstream media or even social media. It doesn’t take much work to see the images that dominate searches such as “hiking outdoors” or “mountain life.”

The people and models in the photos tend to be young, white, and fit. Usually, these people are decked out in expensive athletic wear and using top-of-the-line equipment. Now don’t get me wrong, there’s nothing inherently bad about that. I ascribe to at least one of these facets. But what about everyone else?

Like many in my age group who grew up in the early 2000s, my own viewpoints were shaped heavily by media. Magazines and movies taught me about society’s beauty standard, and just as quickly, that I did not meet it. I was tall and curvy at a young age — even at my most fit (with a hint of a six-pack, however fleeting), I was never thin. Society had held a mirror up to my body long before that bike ride.

But I also learned that many women did not care to humor the standard of beauty perpetuated in media. It was books like The Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants that taught me about friendship, agency, and that beauty comes in all sizes.

I loved Bridget’s height, Lena’s hair, Tibby’s curves, and Carmen’s voice. I loved that they supported one another and though body image was not ignored in the story, it was discussed in a way I hadn’t experienced before.

I am not so idealistic that I advocate for a one-size-fits-all approach to body image; that there is a pair of pants to magically fit us all (as cool as that would be). I think body image is a social construct. At its worst, body imaging is a form of social control, at its best, it’s a spectrum that should strive to empower.

Thinking back to that day biking in B.C., I do not resent my friend. Like all of us, she too struggles with upholding impossible beauty standards. She too, has been pushed and pulled enough times that her impulse is to measure her own worth against mine.

There is something interesting about this particular brand of body trauma, to know, fully, that you are not the best at something — but to find comfort in knowing that at least you are not the worst. In that moment my friend clung to the idea that, though maybe not the best biker herself, she would likely be better than me. She is not alone in this. We all do it.

I think a large part of this trauma response comes from the lack of representation in media, though the efforts of body advocates indicate a gradual cultural shift. When I look at the people who take up space in leisure environments like the hiking and biking trails of the Eastern Slopes, I don’t necessarily see people who look like me.

To me, inclusivity in wilderness looks like bigger bodies in nature. People of different backgrounds, attitudes, and identities. I want to see all shapes and sizes. I want to see varying levels of activity and interest.

The person lounging on a picnic blanket deserves the same respect as the person free-climbing the rocky mountain side. I want to see diverse people, animals, and plant-life. I want to see babies touching grass for the first time, people sunbathing in wheelchairs, goat yoga, and dads teaching their children to bait a line.

I feel strongly that putting parameters around who should access nature experiences is completely counter-intuitive to the human experience. I also want to ‘see’ diversity in nature accessibility in the media — it’s good to be physically out in the wilderness and see various representations, but for those moments when I am not biking through the mountains, but stuck in an office, or on the bus, I want to open my newsfeed and see diversity online.

I urge content creators, marketing teams, and companies to diversify who they hire to model their products — dismantle body politics one plus-size biker photo at a time!

Visibility matters. We all play a role in inclusivity in the outdoors and how people connect with nature. Whether you seek an escape to ease mental health woes, exercise your heart, document the day with photos or connect with someone you love, the outdoors is there for you. Organizations such as Fat Girls Hike and Backcountry Women advocate for more visibility for all bodies and abilities outdoors, especially in the marginalized.

If I could accomplish one thing with the writing of this piece, it’s to call out to those who do not always feel like nature — being in nature — is a place for you. This piece is a giant waving of hands to the world.

If your body is different, if your weight or ability is a factor, your wealth, status, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, or age: any ‘thing’ about you that is different from the images you see around you, then please, hear this: nature is complex and so are we. Get out there, represent, and have fun — and then go share photos of those adventures!

This article was written by Marley Duckett, one of Y2Y’s 2022 story gatherers. These four unique people are sharing personal stories, memories and places related to the special landscapes of Alberta’s Eastern Slopes, often perspectives that are underrepresented in mainstream media. Read other stories in this series.

We are grateful for the financial support provided by Alberta Ecotrust and The Calgary Foundation for our story gatherer series.